| IAAC ERASING BORDERS FESTIVAL OF INDIAN DANCE | |

| Reviews | |

| nytimes.com Review: At Indian Dance Festival, Subtleties in the Sway of a Torso By ALASTAIR MACAULAYAUG. 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

| Aishwarya Balasubramanian Credit Andrea Mohin/The New York Times |

|

Since India has many languages, it would take a true polyglot to comprehend all its poetry. On Friday, when the Erasing Borders Festival of Indian Dance held an indoor program enticingly called “An Evening of ‘Poetry, Danced’ ” at Pace University’s Schimmel Center, the audience was given words in five different languages. If we accept Frost’s theory that poetry is “what is lost in translation,” probably most of those present lost a great deal. Much, however, remained. The five numbers - each a solo - certainly showed five different dance languages, and four demonstrated language in high stages of sophistication. The written program notes drew attention, as is customary in Indian dance, to the subject matter of each item; but often where we saw poetry, it was in pure style rather than in specific communication. The music was taped: a cause for regret, though forgivable when we heard of the trouble in obtaining visas for these dancers. |

|

|

|

| Pallavi Krishnan Credit Andrea Mohin/The New York Times | |

We could feel something of that in the opening piece, “Ajapa Natanam,” danced in the Bharatanatyam style of the southeastern state of Tamil Nadu. The female dancer Aishwarya Balasubramanian responded to a poem in the Telugu language about the male god Shiva. The notes said, “The dancer alternates among representing herself, the devotee longing for an experience, the sculptor, iconic sculptures, and finally the spontaneously pulsating ocean of consciousness - the unseeable dance.” |

|

|

|

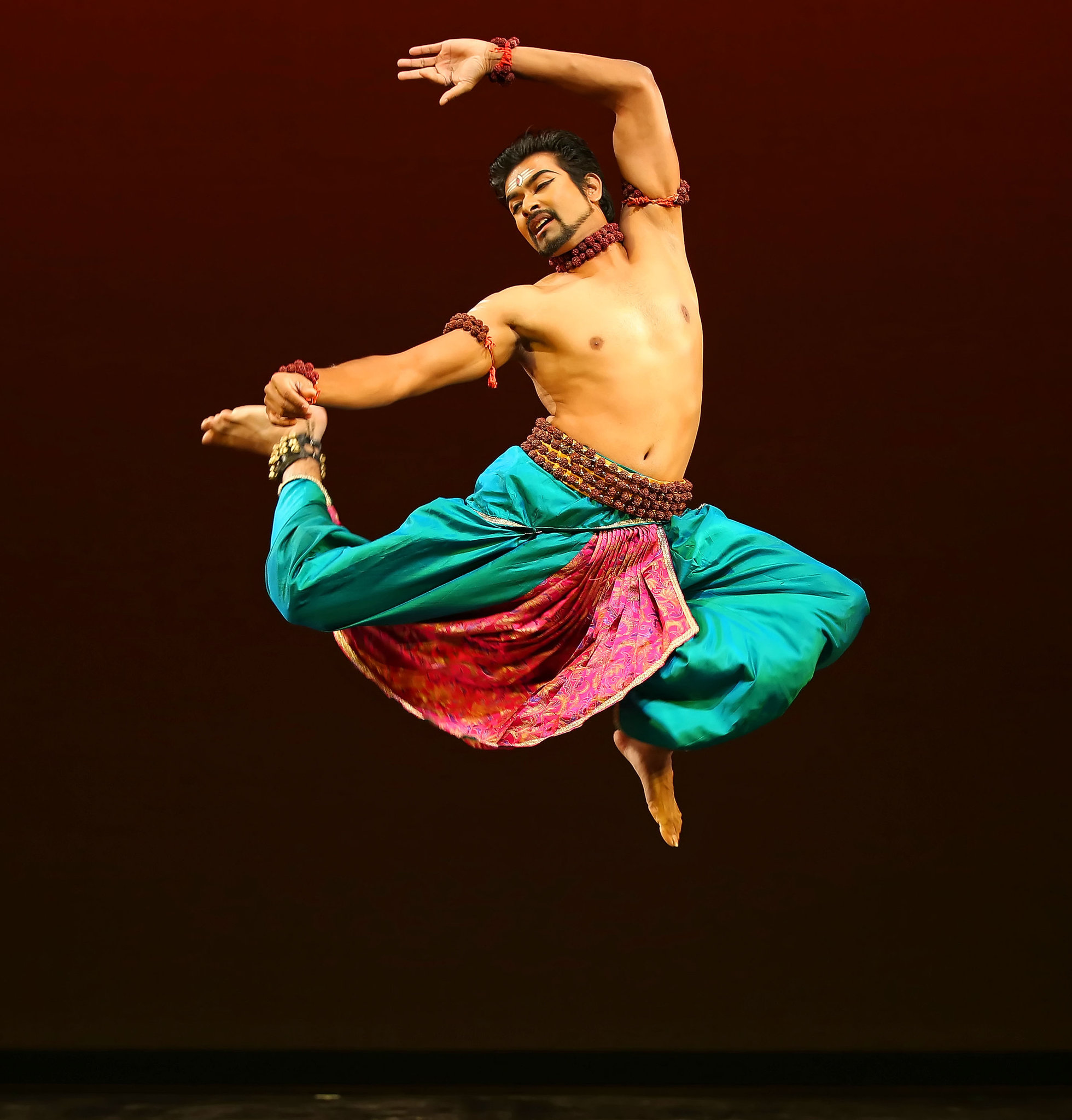

| Rakesh Sai Babu Credit Andrea Mohin/The New York Times | |

| Only fragments of that were apparent just from watching, yet the experience was rich. Bharatanatyam is the most geometrically multidirectional of the Indian genres - in the nritta sections, Ms. Balasubramanian turned in quick succession to address right, left, behind, ahead, above and below, as well as various diagonals - and the sharp transitions are often not just exciting but also powerfully expressive of the dancer’s setting herself within a larger context. All the while, feet, arms, thighs and head make their vivid contributions; the precision of Ms. Balasubramanian’s footwork was a keen pleasure in itself. |

|

|

|

| Aparupa Chatterjee Credit Andrea Mohin/The New York Times | |

| In “Pingala,” the dancer Pallavi Krishnan played a wealthy courtesan who awaits her clients, confident of her power to lure men; when, as the program notes said, “her haughtiness turns to anxiety and despair” she then “contemplates the ephemerality of personal beauty and riches” - and focuses to attain solace and redemption on Lord Rama. Based on a poem in the Malayalam language, this was performed in the Mohiniattam idiom of the southwestern state of Kerala; and, unlike the majority of the Mohiniattam dances I’ve seen, it emphasized aspects of abhinaya. |

|

|

|

| Sanjukta Wagh Credit Andrea Mohin/The New York Times | |

Although I may have misread the dance details onstage - I saw the dancer seeming to pluck petals and place them in her basket, not a point apparent in the notes - I was constantly absorbed. There appears to be no end to the subtleties of the swaying of the torso in Mohiniattam - curves, tilts and arches all follow one another in a legato stream - and much of it is propelled by the thigh. Footwork carries the dancer in other patterns with different meters. Nothing was more fascinating on Friday than “Mahadeva,” performed in the Chhau style (unfamiliar in the West) from Odisha by the male dancer Rakesh Sai Babu. Again Shiva was the subject - Shiva with his dance of creation and destruction, the most philosophically profound of the many dances that pervade Indian thought. As when Mr. Sai Babu showed Chhau in the open air two weekends earlier, the music was the strangest to Western ears: discordant pipes and drums. Also from Odisha was “Brajaku Chora,” an Odissi dance style. On the one hand, this - danced by Aparupa Chatterjee - was the evening’s most successfully and charmingly communicative number: a two-way dance in which Mother Yashodha tries to lull the prankster child Krishna to sleep while he resists. On the other, this lover of Odissi felt that the dance did least to show us what this genre can achieve in terms of sumptuous shape and plasticity. |

|

| URL:http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/31/arts/dance/review-at-indian-dance-festival-subtleties-in-the-sway-of-a-torso.html?_r=0 |