MOVIES THAT MATTER

By Lavina Melwani

September 2015

You Can Now Choose IQ over Item Number, Matter over Muscle... The times they are a-changin’, admits Bollywood. And about time, say an ever increasing number of moviegoers. Even as the industry’s formula films continue, there is an influx of gems with themes that range from the gritty and shocking to quirky and sensitive and socially relevant. These films are competing with the clichéd staples to send ripples across the industry. We explore this brave, new world of Indian cinema and the factors powering its rise.

Is Indian cinema growing grey cells? A conscience? More empathy? Just this year I’ve watched a whole lot of films which made me feel that Indian cinema, usually flippantly boxed together as Bollywood, is maturing, developing a heart and a soul.

(Left) Titli: In the badlands of Delhi’s dystopic underbelly, Titli, the youngest member of a violent car-jacking brotherhood, plots a desperate bid to escape the ‘family’ business.

NYIFF showcase

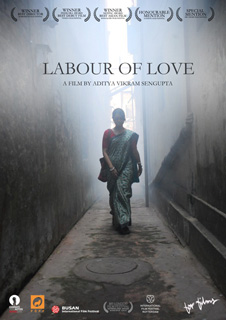

In recent times there have been thought-provoking films like Court, Killa, Titli, Fandry, and Shahid, themed on social issues that remained with viewers long after they left the theater, in the manner of old powerful gamechangers like Garam Hawa, Ankur, and Manthan. This year’s New York Indian Film Festival (NYIFF) showcased a host of strong films like Margarita with a Straw, Gour Hari Dastaan, City Lights, Yeh Hai Bakrapur, Labour of Love (which won several awards), and the children’s films Kaakka Muttai, and Elizabeth Ekadashi which took on a range of thought provoking, sensitive issues from religious politics to class inequities to women’s rights.

(Left) Labour of Love (Asha Jaoar Majhe), winner of the National Award - Golden Lotus Award for best debut film, set in the crumbling environs of Calcutta, is a lyrical unfolding of two ordinary lives suspended in the duress of a spiraling recession.

Labour of Love shows a love story in a very different way. This Bengali film (Asha Jaoar Majhe) by Aditya Vikram Sengupta won the National Award - Golden Lotus Award for Best debut film. It also won the FEDEORA Award at the Venice Film Festival and the Best Director Award at the Marrakech Film Festival. As Gayatri Gauri wrote in First Post, “Technically, Labour of Love is a Bengali film. But actually, this debut film by Aditya Vikram Sengupta, transcends all spoken languages and makes a voyeuristic camera a powerful spokesperson.... Here’s a couple caught in the drudgery of making a living at a time when the uncertainty of a job is driving people to suicides. Their deliberate calm exteriors, refusing to reveal the inner world, is evocative of millions of people who brave every challenge with quiet acceptance.”

(Right) Kaakka Muttai.

In Kaakka Muttai, slum children yearn to eat pizza in the new parlor which has come up in their old playground––but one pizza costs more than the family’s monthly income. Rough Book takes on the issue of education and the rat-race competition to get into IITs. What is real learning about and how can a dedicated teacher keep her integrity?

In place of Bollywood’s standard, masala-laden paeans to beauty and the box-office, viewers got to see some very brave movies. ChotoderChobi (Short Stories) is the complete antithesis of commercial Indian cinema’s fascination for six-pack abs and impossibly perfect curves. This Bengali film follows the life of Khoka (played by Dulal Sarkar) and Soma (Debalina Roy),

two dwarfs, and their bitter-sweet life.

It was a brave choice by filmmaker Kaushik Ganguly, for would audiences want to sit through such a difficult love story when in real life, they typically shy away with revulsion from these little people with their midget bodies? Arguably the strongest point of this film is the empathy it arouses in the viewer. Little surprise then that this film won the National Award for Best Film on Social Issues, and the best actor award for Dulal Sarkar at IFFI in Goa.

(Right) Margarita with a Straw is about a rebellious young woman with cerebral palsy who leaves her home in India to study in New York, unexpectedly falls in love, and embarks on an exhilarating journey of self-discovery.

Bollywood has rarely produced films that delve realistically into the lives of the disabled, so sex for the disabled would be an absolute no-no. Yet, Shonali Bose’s Margarita with a Straw takes on both these taboo topics. Her protagonist Laila, played by Kalki Koechlin, has cerebral palsy

but hungers for a normal sex life.

“The utterly remarkable thing about Margarita is that Laila isn’t a differently abled person. She’s a person who is differently abled. The order of the words matters. The human being comes first, the condition only later,” wrote Baradwaj Rangan in his insightful review in The Hindu. He goes on to say, “And then, we get the film’s biggest googly. In New York, Laila meets Khanum (a no-nonsense Sayani Gupta), who’s blind. The film takes on another disability–but again, there’s not a trace of stereotype, not a shred of self-pity. Laila is …slowly drawn to Khanum and discovers she’s bisexual. In her audience-friendly handling of hotbutton issues, Bose is a version of Mani Ratnam.”

In Haraamkhor, a school teacher has more than an academic interest in one of his female students.

Haraamkhor, a film by Shlok Sharma, addresses a shocking subject––a married school teacher who has an affair with his under-age student. The unmatchable Nawazuddin pulls it off, being at times charming, at times stoic and amoral. It’s only when you feel repelled by him that you know your conscience is alive and well. Now here’s a fable for our times!

Rough Book, a film by Ananth Narayan Mahadevan, is the story of a teacher who wants to change the system—even if it means losing her job and her place in society. Tannishtha Chatterjee gives a fine performance as a physics teacher who takes on the educational bigwigs to save the mixed bag of students in the D division, known as Duffers.

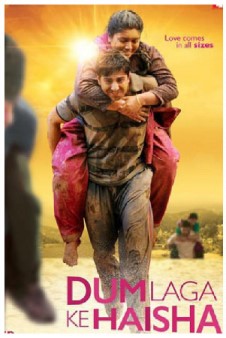

(Right) Dum Laga Ke Haisha: Even commercial Bollywood is bucking trends by treading into stories that don’t require an impossibly gorgeous leading lady.

Dum Laga Ke Haisha was a surprise package from the Big Daddy of old style Bollywood cinema, Yashraj Films, evidence that even commercially oriented production houses can make socially conscious films and still keep their audiences happy. The film has done phenomenally well at the box office even though it has a heroine who is overweight and far from fabulous. Indeed, DLKH has a striking premise—that excess weight and good looks have little to do with physical attraction, and love comes in all sizes.

NYIFF was started on the premise of screening independent, art-house, alternate films—cinema that highlighted real situations, addressed real issues, and reflected the lives of real people. I asked Aroon Shivdasani, Director of the Indo-American Arts Council which organizes NYIFF, if there was a trend for issue-based films.

“The mass market for Indian films has traditionally been escapism or melodrama based on a thus far ‘winning formula,’” says Shivdasani. “NYIFF has contributed greatly to the visibility, acceptance, and enjoyment of independent cinema over these 15 years that we have doggedly presented films that expose, discuss, or just present important social issues.”

Arthouse cinema down the years

Escapism continues to draw in huge audiences in the Indian film industry. After all, an item dance number, exotic locales, flashy cars, and sexy Bollywood stars are almost as relaxing as a glass of vino after a hard day of work!

Just for a moment though, pause to think about the 1950s, the Golden Age of Indian cinema. Raj Kapoor’s Awaara, V. Shantaram’s Do Ankhen Barah Haath, and Bimal Roy’s Sujata were films that appealed to

the sensitivities of viewers, touching and memorable in their storytelling and unforgettable performances.

Now, in that same spirit many contemporary filmmakers seem to be going out on a limb to create thought-provoking films, even exploring distinctly uncomfortable themes (but which increasingly now find acceptability across social strata). Are Indian cinema and the audiences who watch such movies maturing as a whole? I talked to some film experts to get the behind-the-scenes story on this fascinating new trend.

While films of the 1950s focused on larger social issues, film critic Aseem Chhabra points out that this was not the only era that

produced memorable Indian cinema.

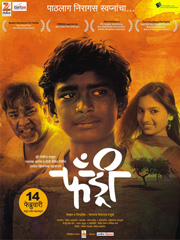

(Left) Love, the most beautiful

emotion in all living

creatures that God has made, knows no bar, caste or boundaries, and is the central theme of Fandry.

“Look at the New Wave/ Parallel Cinema of the late 60s and through the 70s—works by filmmakers like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Girish Karnad, M. S. Sathyu, Girish Kasaravalli—I think that was the real golden age of socially relevant cinema,” says Chhabra. “Things changed in the 80s and 90s when NFDC (National Film Development Corporation) stopped funding films. But in recent times there have been indie films with strong social messages—look at what is happening in Marathi cinema, with films like Shalla and Fandry. Even in mainstream Hindi cinema, films like Queen are sending a strong message for change.”

Are art films a thing of the past or do such films continue to be made? Says Chhabra, “We have a very strong indie film movement exploding in India—works by Anurag Kashyap, Dibakar Banerjee, and some very relevant and brilliant films in various regional languages, especially Marathi. Indian cinema is evolving, but it continues to deal with serious important

social issues.”

“Through the years we have had filmmakers in Hindi and regional cinema who have addressed larger social and political discourses,” says Dr. Satish Kolluri, Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Pace University. “I don’t think that trend has stopped. Just a look at the National Award Winners over the years is a testament to the cultural diversity of films from different regions which have made a mark.”

Kolluri points out that art cinema or parallel cinema in the 1980s was dominated by filmmakers like Shyam Benegal, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, and Aravindan in Malayalam cinema, even as that particular decade produced some of the worst films in Bollywood, peppered now and then by gems from Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Sai Paranjape, and Basu Chatterjee.

Says Kolluri, “Art films can never be a thing of the past because we will always have filmmakers who are in love with the medium of cinema and who will continue to make meaningful films.” He adds, “On a lighter note, these days any film in comparison to the ones made by Farah Khan and her illustrious brother Sajid Khan and their 100 crore ilk will stand out as ‘art films’! But seriously, we are witness to a democratization of ‘Hindie’ film making in India which means family dynasties or select individuals no longer rule the roost in terms of producing films, and corporates/industry houses have taken their place to a large extent. The subjects tackled by filmmakers in the present have brought back the realism of the 80s art cinema but this time on steroids, if you will, because they are much edgier and grittier, and tackle head-on middle class moralities.”

Kolluri goes on to observe that during the 1970s there was a small group of highly accomplished actors from FTII (Film & Television Institute of India) and NSD (National School of Drama) who dominated the art/film festival circuit, stars like Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Om Puri, and Smita Patel who actually helped alter the stereotyped image of the Bollywood star.

Ask Tejaswini Ganti, an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and its program in Culture and Media at New York University, and she says that “socially conscious” is a subjective term and very loaded, for in the history of filmmaking in India, most filmmakers have gone to great trouble to present themselves as socially conscious.

“This was because they were made to always feel defensive about their filmmaking practices from the nationalist movement when Gandhi spurned movies and lumped filmmaking with other ‘vices’ like horseracing and gambling, to Nehru who put in place an entire cultural bureaucracy that ignored or disdained filmmaking,” she says. “All India Radio in those days was reluctant even to play film music and bureaucrats were always asking filmmakers to make socially relevant cinema and uplift the masses.”

Ganti points out that while the US government from the 1920s onward saw the potential of cinema both in terms of economics and “soft power” and created the conditions necessary for Hollywood’s expansion and global dominance, the Indian government with its paternalistic attitude toward its population was only interested in cinema as a tool for development or as a vice that needed to be policed and regulated.

Looking beyond Bollywood

Aseem Chhabra has another explanation for the sudden spurt in issue-based films: “There are many young filmmakers, scriptwriters who are looking beyond Bollywood for inspiration. They are seeing Asian, European, and American films but then are rooting their stories in the Indian context. They often are troubled by social inequalities and other issues in India. We live in a global village, and ideas and themes inspire people from all over.”

While for years and years the Indian film industry survived on a basic formula for box office success, Kolluri observes that the “winning formula” doesn’t always work these days if the story has basically remained the same (notable exceptions being films top lined by the Khans!).

He says, “Audiences have become more demanding for films that take them out of their comfort zones and make them think of issues without sacrificing their entertainment value. My Big Fat Indian Wedding,

Taare Zameen Par, and The Ship of Theseus are recent

examples. The stories being told are more real and

authentic and less escapist and fantastic because the filmmakers are true to their experience and

class origins. That being said, a director like Bhansali makes ‘entertaining’ cinema that doesn’t work for most of the audiences.”

So maybe it’s a case of perception, of whether the cinematic glass is half empty or half full!

Change is good, says a young India

Yet things have certainly changed for the better and our increasingly globalized world with its travel, film festivals, social media, and, of course, the Internet have seen to that. Ganti points to the changing structures of exhibition and distribution “that allows a greater variety of cinematic voices/films to be able to be screened/heard. There always has been a great variety of topics and styles in Indian filmmaking over

the years, but what is different now is that there are more venues and opportunities for audiences to encounter this variety.”

Since the millennium the explosion of film festivals is enabling a greater variety of filmmaking to find an audience. Ganti says the important point to note when it comes to India is that the number of films

certified for exhibition—the official production numbers—is not the same as the number of films released. Many never reach a theater and pubic viewership.

She says, “This has always been the case—that was the tragedy of NFDC—they funded many fine films, but the government never invested in an alternative distribution and exhibition apparatus. Even now more films are made than are distributed—but what is interesting is that the ‘indie’ films, such as Anurag Kashyap films, are being financed and distributed by the very mainstream film institutions—UTV, Yashraj, and Eros.”

Once, it was only a small, elite viewership located in urban and semi-urban settings who got to or want-ed to watch “arthouse cinema.” But that is changing fast now, says Kolluri, with the advent of “Indie” filmmakers who may or may not choose to work with bankable “stars.” Ironically, now it’s often the celebrities who want to work with the likes of Kashyap,

Kamat, Basu, and Bannerjee—the so-called “outsiders”! Clearly, the lines between “commercial” and “arthouse” cinema are blurring—and about time too.

Such groundbreaking shifts within the industry also signal seminal changes in audience tastes.

India’s demographic profile today is dominated by

the young. This large segment of the population is

mobile, aspirational, and open-minded, ready to listen to new stories and willing to explore films made

even in unfamiliar languages.

There’s also the diaspora, spread across the

world, whose exposure to world cinema makes them

an audience open to watching Indian films in

diverse languages.

A stellar group of filmmakers at the New York Indian Film Festival.

Watch the names on any credit roll of an Indian film today and you see something wonderful—it really does read like a map of India, peppered with names from several states. Cinema reflects a nation and its people, its aspirations and beliefs. And in good cinema, talent trumps everything else. It bodes well for the

Indian film industry that movies are increasingly

brave, individualistic, and not tied to any musty formula. Finally, Indian filmgoers have choice: they can opt for IQ over item number, and matter over muscle—but all still told to the beat of beautiful film music, of course!

Lavina Melwani is a New York based journalist for several

international publications. She blogs at www.lassiwithlavina.com . Follow on Twitter @lavinamelwani.