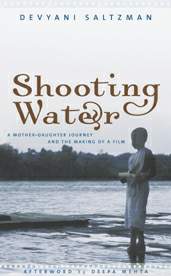

Shooting Water: A Mother-Daughter Journey and the Making of a Film, by Devyani Saltzman (Key Porter Books), 278 pp

Shooting Water: A Mother-Daughter Journey and the Making of a Film, by Devyani Saltzman (Key Porter Books), 278 pp |

THE HOUR, Montreal

November 10th, 2005 THE HOUR, Montreal

Shooting Water, by Devyani Saltzman

Dry spell

Geeta Nadkarni

Shooting Water, by Deepa Mehta's daughter Devyani Saltzman, takes precedence over everything

My virginity's growing back and I blame Devyani Saltzman. Ever since I received my copy of Shooting Water, I've been unable to respond to Himself's advances with anything more than an "Um-hmm, later babe." For once, I'm actually intent on reading for work instead of misplacing my glasses and having procrastination sex.

Yes, the book is that good.

Part of the reason I'm so fascinated is because the story behind the story is a thread in my own personal history. Devyani's mom, acclaimed independent filmmaker Deepa Mehta, is one of my heroes. Her Elements Trilogy (Fire, Earth, and finally Water) sparked the awakening of my political and social consciousness back when I was a university student in Mumbai.

The fact that Water is finally hitting our screens on Nov. 4, five years after government-supported Hindu fundamentalists burned down Mehta's sets in Varanasi and threatened to kill her and some of the lead cast, is something of a miracle. Shooting Water explains why.

But that's only one facet of Saltzman's impressive memoir. A larger part of the story deals with the troubled relationship between mother and daughter. When Devyani was 11, her parents got divorced and she was forced to choose who she would live with. She picked her dad. It was a decision that would forever strain the bond between her and her mother - Shooting Water was supposed to be a way for Mehta and Saltzman to reconnect and bury their past.

The book itself is about many things: the making of a film, Indian politics, mother-daughter tensions and the coming of age of a Jewish-Hindu, Indo-Canadian girl who must figure out who she is. In a lesser writer's hands, the narrative could have gotten either overly cluttered or stayed dry and factual, but 25-year-old Saltzman knows exactly what she's doing.

Her voice is powerful but at the same time so intimate that you could be forgiven for thinking that she's writing certain passages only for you. And the fact that she comes from a household where "film was [her] second language, before Hindi" shows in her writing, which is vivid and enticingly visual.

Unfortunately, despite the fact that I'm done reading the book now, I'm still not getting any. All I hear from the side of the bed that previously read only in French is, "Quoi? Laisses-moi tranquille. I'm at the good part - the Hindu mob..."

|