|

|

| Shonali Bose’s AMU - May 25, 2007 |

| |

AMU

A film by

Shonali Bose

Official Selection: Berlin Film Festival 2005

Official Selection: Toronto Film Festival 2005

Official Selection: AFI Film Festival, 2005

Winner: Fipresci Critics Award 2005

Winner: National Award, India, 2005

Running Time: 102 min.

www.amuthefilm.com

|

Publicity:

Gitesh Pandya

Box Office Guru

gpandya@boxofficeguru.com |

| CREDITS |

|

CAST

Kaju................................................................Konkona Sensharma

Keya............................................................................Brinda Karat

Kabir.........................................................................Ankur Khanna

Tuki.............................................................................Chaiti Ghosh

Grandmother................................................................Aparna Roy

Uncle.........................................................................Ashish Ghosh

Aunt............................................................................Ruma Ghosh

Gobind...................................................................Yashpal Sharma

Leelavati..................................................................Lovleen Mishra

Chachaji...................................................................Brajesh Mishra

Arun Sehgal..............................................................Bharat Kapoor

Meera Sehgal............................................................Lushin Dubey

KK...........................................................................Rajendra Gupta

Shanno Kaur.........................................................Ganeve Rajkotia

Gurbachan Singh...........................................................Kuljit Singh

Amu.................................................................................Ekta Sood

Arjun............................................................................Harshit Sood

Durga.........................................................................Mohini Mathur

Shanti Kumar......................................................Kirandeep Sharma

Widows.......................................................................Amita Udgata

Kusum Haider

Neel..................................................................................Avijit Dutt

Lalitha (L)..................................................................Subhashini Ali

Siddharth...................................................................Susmit Sarkar St

Stephanians.....................................................Lara Ahsan Chandni

Maxwell Chhetry

Subhashish Mukherjee

Gobind’s children.................................................................Bublee

Salmaan

Pappu.......................................................................Sanjay Kumar

Train passengers......................................................Charu Kasturi

Sunil Pandey

Nitin Gupta

Ravishankar

Vimala Ramkrishnan

Sikh with haircut.......................................................Inderpal Singh

Mob leader..............................................................Santosh Kumar

Man with radio..............................................................Vijay Kaliya

Child.......................................................................................Tanya

Salsa party.............................................................Kajori Dasgupta

Monish Dasgupta

Bejoya Pain

Bela...................................................................Sadhna Bannerjee

Ramu.................................................................Narendra Chauhan

Sehgal Lunch guests.....................................................Anjali Malik

Jasbir Malik

Gaurav Raina

Veena Sawhney

Indira Dayal

Indu Wahi

Ashok Gupta

Meera Juneja

Ranjit Das

Anjali Chawla

Kavita Das

Vijay Sawhney

Mala Gupta

Vaishnavi

Workers Leader.................................................................Bijju Naik

Sexologist......................................................Bikramjeet Kanwarpal

Miranda House girl...........................................................Surkh Raj

|

| CREDITS |

|

CREW

Writer/Director/Producer................................................Shonali Bose

Executive Producers..................................................Bedabrata Pain

Gurdip Singh Malik

Associate Producers..........................................Geetha Ravishankar

Uma Chakravarthi

Co-Producers.....................................................................Aidan Hill

Atiya Bose

Director of Photography..........................................Lourdes Ambrose

Production Designer.................................................Ayesha Punvani

Film Editor........................................................................Bob Brooks

Sound Recordist and Sound Design...........................Resul Pookutty

Assistant Director..........................................................Neelima Goel

Line Producer....................................................Sanjay Bhattacharjee

Script Supervisor.............................................Shubha Ramachandra

Costume Designer.......................................................Sujata Sharma

Music...........................................................................Nandlal Nayak

Creative Assistants.....................................................Ali Abbas Zafar

Mandakini Dubey

Production Manager.....................................................Kaushik Guha

Financial Controller........................................................Tina Nagpaul

Production Coordinator..................................................Sunil Pandey

|

| SYNOPSIS |

|

Though it starts out as a standard “back to the roots” story, Shonali Bose’s feature debut Amu becomes a mystery of both personal and political implications.

Amu is the journey of Kajori Roy, a 21-year-old Indian-American woman who has lived in the US since the age of 3. After graduating from UCLA, Kaju goes to India to visit her relatives. There she meets Kabir, a college student from an upper class family who is disdainful of Kaju’s wide-eyed wonder at discovering the “real India.” Undeterred, Kaju visits the slums, crowded markets and roadside cafes of Delhi. In one slum she is struck by an odd feeling of déjà vu, leading soon to nightmares. Kabir gets drawn into the mystery of Kaju’s past, which is only deepened when he discovers that she is adopted.

Meanwhile, Kaju’s adoptive mother – Keya Roy, a single parent and civil rights activist in LA – arrives unannounced in Delhi. She is shocked to discover that Kaju has been visiting the slums. Although Kaju mistakes her mother’s response as typical Indian over-protectiveness, Keya’s fears are deeper rooted.

Slowly Kaju starts piecing together what happened to her birth parents, discovering that her adopted mother has been lying to her for her whole life. What is the truth? Why was it suppressed? As Kaju and Kabir undertake this quest for personal discovery, it leads them unexpectedly to tragic events in India’s history more than twently years ago: the massacre of thousands of people of the Sikh faith in the capital city of Delhi. In a searing climax, the young people are forced to confront the reality of the past and how it affects the present.

|

| DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT |

|

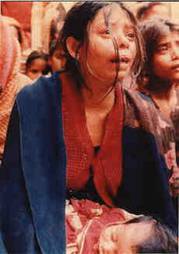

I was a 19 year-old student in New Delhi, India, when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards at the end of October 1984. In the days and nights that followed, thousands of people of the Sikh faith were massacred as “retribution” in a carnage organized by those in political power. The city burned. Like many other people, I worked in the relief camps where survivors languished for months. One of my jobs was transcribing postcards from widows to their relatives, writing down their stories of the horrors that had taken place. It was unforgettable.

Three years later, a personal tragedy compelled me to leave India and I came to the US as a graduate student. Halfway through my Ph.D. at Columbia University in political science, I realized that I wanted to make films about the issues that I was studying. Academia felt too removed. I wanted to engage with people about struggles and histories that they did not know.

UCLA Film School – the crucible that made me into a filmmaker was hectic and traumatic. I gave birth to three films and two children during my MFA program and emerged in 1997 knowing more about diaper rash than about how to make a feature film! Making shorts in the safe environs of film school is one thing; making a full feature in the competitive and hostile “real” world is quite another. In 1999 when my younger son was 2 and the adult world seemed a tad closer, I decided to take the plunge and discover if I was even capable of writing a feature instead of just cherishing the life-long dream.

Everyone advised me that a first film should be marketable – a horror film, comedy, or love story. Definitely not something political! Bollywood, I was told, was “in”. But the story of the riots and relief camps of 1984 insisted on being told. I knew that was the film I had to make. No matter how hard it was going to be, this was the story I had to write and the film I had to make – to bring to light the suppressed history of that genocide. And so Amu was born.

It took me four years to write and rewrite Amu and look for the financing, all the while bringing up my children as a full-time mother. As a writer I felt I had to write about that which was most painful for me in my life, and so Amu also became the story of a mother-daughter relationship – a story of maternal loss, the same tragedy that had brought me to America many years ago. It was a deeply personal story, which made the countless rejections and closed doors even harder to face. Most Indian producers felt that it would not be possible to shoot such a film, that if it got made no one would want to see such a film, and that, if released, the theaters would be burned down.

Finally, in early 2003, an independent producer promised me the entire budget. Midway through casting, he emailed me to say that Amu was too risky for them, and they would now be investing in a Bollywood film instead. In one fell swoop, all of the money was withdrawn. That night at the kids’ bedtime, as we performed our ritual of sharing our “good thing, bad thing of the day,” I told them my “bad thing.” My younger son immediately handed me his tooth fairy money and my older son, the pocket money he had saved for the last 10 weeks. Later that night at the dining table, when I told my husband what had happened, he passed me a letter he had got in the mail that very evening. It was a royalty check from NASA (where he is a scientist) for his invention of the world’s smallest camera. There was no debate about where the money should go! Armed with this princely sum from my family (barely a tenth of what I needed)

I acted as if I had the entire amount and decided to go ahead with pre-production. Miraculously the rest fell into place while I chose locations and actors during the children’s school vacation.

Making Amu was very painful and exhilarating at the same time. I had to leave my family in LA and go to India. I promised my kids I would be back after shooting over 10 Sundays (and I was). The first day that I walked onto the set I was terrified – I was the only person in the whole cast and crew who had never worked on a professional set. The last set I had been on, my husband was the production manager picking up free bagels from Western Bagels Too and my classmates and close friends were the grand six person crew!

The process of shooting was difficult enough with the daily technical challenges like working with recalcitrant toddlers and shooting sync sound in noisy marketplaces and train stations amidst crowds of onlookers. But the first real threat came when I had to shoot the riot sequences. I had deliberately delayed these scenes until the end, and the entire cast and crew had signed contracts stating that they would not speak to the press or to anyone about the film. Still, within an hour of starting to shoot the riot sequence, some hoodlums showed up on the set with a “message” for me from their boss – a well-known politician who had been involved in organizing the killings in ’84. “A film on the 1984 riots cannot be made. Shut down immediately.”

“Riots? What riots?” I said. “This is a love story with some random violence in the background. I’m from America – I have no idea what you’re talking about!” I knew that my diplomacy and feigned naiveté could only buy me a little time. We got the bare minimum and stopped shooting the “riots.” Within a week, I was back in LA with my negative.

As the producer of Amu, the work didn’t end for me with picture lock. In India the Censor Board took three months to clear the film. If I ever had any doubts that a cover-up of history had taken place, they were set to rest when the Censor Board informed me that I would have to change five crucial lines of dialogue into something “acceptable.” They were all lines that dealt with the complicity of the government in the violence. Instead of changing and redubbing the lines I decided to mute the sound instead. In Indian theaters – where the film screened to packed houses – audiences watched the actors playing the Sikh widows silently mouth their indictment of the state. And a whisper – “censor, censor” – would go through the theater as audiences realized what had happened. Far more pernicious than these cuts was the Censor Board’s verdict that the film would have an “A” certificate (equivalent to an NC-17 rating in the U.S.). I asked them why, as there was no sex and violence in the film. They replied, “Why should young people know a history that is better buried and forgotten?”

Such history cannot be buried and forgotten. Young people cannot make their future or understand their present without knowing the past. Today, 22 years after an elected government massacred its own people in full view of the world, no one has been punished. And as a result, the cycle of violence has continued against other communities. What kind of political system is this in which those in power can get away with such crimes again and again? This is the question Amu leaves the young protagonists with as they walk down a railway track into the future. This is why I made Amu.

The reception of the film has exceeded my wildest expectations. I had no idea how unknown this history was until I faced questions from audiences all over India. Since young people were barred from seeing the film in theaters, I went to schools and colleges and their responses were the most moving and powerful. My biggest fear was how the Sikh community would receive the film. Would they turn around and say that this was too painful – let bygones be bygones, why was I putting salt in the wound? I had met with the survivors in Delhi when I was writing the script and received their blessing. But I had no idea how the community abroad would react. I needn’t have worried. They have shown their support in myriad ways, including raising money for the release of the film. In spite of various offers for a theatrical release we made the decision to self-release the film so that we could control the kind of release it was. We knew – from the festival experience – that this was a film that appealed to wider audiences beyond the South Asian community. We did not want to take the chance of the film being shelved or postponed or given short shrift because a distributor found something else more “appealing” as can be the case with independent film makers. So we partnered with our producers rep – Emerging Pictures – to release the film and started the cycle of fundraising again. In Toronto, I participated in radio-thons where Sikh taxi drivers called in pledges of $50 and a $100 each. As a result of this grassroots support, Amu will release in 10 cities across Canada and cities across the US beginning in May 2007.

I started this journey not knowing if I could make a film. I have come through this fire with a passion to tell more stories. The film I am working on now is called Chittagong: Strike One (the first of a trilogy which starts in 1930 and ends in the present). It is the true story of a schoolmaster in Bengal who organized 68 teenagers to stand up to the mighty British Empire in 1932. Inspired by the Irish Easter Rebellion, their motto was to “do and die.” They felt that if, as in Dublin, they could liberate one town in Bengal, they could set an example for the whole of India to rise up and overthrow their colonial rulers. After defeating the British army in a pitched battle, the group went underground, though many would go on to be caught and imprisoned. They carried on their resistance, however, because of the participation of two sixteen-year-old girls. Chittagong: Strike One is the dramatic enactment of this powerful and successful resistance – which finds no mention beyond one sentence in Indian history books, as it was reviled as “revolutionary terrorism.”

The youngest participant in the uprising was 14-years old at the time. I interviewed him on camera in August of 2006 when I was visiting India, and promised him that this story would be told to inspire the youth of today. He gave me his blessings. At the age of 92 he smiled toothlessly into the camera and with glistening eyes reminisced about how he had felt during the Battle of Jalalabad, as he confronted death. “As I faced the British bullets my mother’s face swam before my eyes – would I see her again?” he said. Two weeks after the interview, he died. He was the last survivor of Chittagong and should have been a national hero, but the mainstream news didn’t even report his death. But Chittagong will ensure that Jhunku Roy’s story and the stories of Masterda, of the young women and the teenagers of the struggle, don’t die with him. My promise to him has made this film a commitment beyond me. Like Amu I am compelled to make it. And I will.

Shonali Bose

|

| CAST BIOS |

|

KONKONA SENSHARMA – KAJU

Sensharma is the rising young star of new Indian cinema. Her acclaimed performance in Mr. and Mrs. Iyer won her the National Award for Best Actress in India in 2003. As a teenager she made a mark in Bengali cinema with Titli and Ek je achey Kanya. Her performances in Page 3 and 15 Park Avenuehave been similarly praised. She has also demonstrated a flair for comedy in Chai paani etc and Mixed Doubles. Her most recent role in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Omkara – a mainstream Hindi musical adaptation of Othello – has shown her versatility as an actor and her ability to hold her own with the top superstars

Sensharma: “I was very nervous when I went for the audition for Amu as I was dying to do the role. I had read and loved the script.”

Bose: “I had auditioned close to 50 Indian-American actors in the US for Kaju as her authenticity as an Indian American was very important to me. Koko was by far the most superior actor of any Indian I knew or had come across of her age. She had to be Kaju. I took her to LA where she lived with us for a few weeks and trained in the American accent and got immersed in “Kaju’s life” in Los Angeles.”

ANKUR KHANNA – KABIR

Khanna is an actor and filmmaker. Amu is his feature film debut. He has acted in various short films and has a theater background from St. Stephens, Delhi University. His short film on football, called Bare, was selected for the Berlinale Talent Campus at the 2005 Berlin Film Festival. After Amu, Ankur will be seen in Naseeruddin Shah’s directing debut film Yun Hota To Kya Hota.

Khanna: "When I read the script I found it incisive and the commentary layered, but what really convinced me was Shonali herself. Her conviction and sheer sense of enterprise for what, at that time, seemed fairly daunting, almost impossible to do....."

Bose: “Ankur is the first and last person I auditioned for Kabir. Because as soon as I saw him, I realized he was everything I had written and more. So when he got hepatitis during pre-production and I was urged to recast, I refused to. Instead we completely reworked our schedule and put all his scenes at the end. It was very brave of him to do it when he was so weak.”

BRINDA KARAT – KEYA

Amu is the Karat’s acting film debut. Her last venture into acting was in theater in the 1960’s as a college student. Karat has been a leading women and workers activist for the last three decades. She is a central committee member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). She worked in the relief camps in 1984. Karat is also Shonali’s aunt, though has been very much like a mother.

Karat: “I agreed to play Keya because the script is so powerful and so rooted in reality. Furthermore it is not just dealing with an issue that I feel strongly about but is a beautiful mother-daughter relationship. I relate to the character of Keya, to a mother who will do anything for a child even when she is not biologically her own.”

Bose:“I had heard from my mother that her sister was a very talented actor but had eschewed an acting career for politics. She also had the vulnerability and pain and depth in her eyes, in her face that I wanted for Keya. We did various screen tests before we both felt confident that she could pull it off. But I was terrified about how the flip of authority situation would go down! I needn’t have worried. She took direction very well.”

YASHPAL SHARMA – GOBIND

Yashpal Sharma, a leading name in Hindi films, is a graduate of the National School of Drama and has worked in more than 20 films, including Lagaan, Apaharan, Gangajal, Bawandar, Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Ma, Ab Tak Chhapan, and Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi. He has worked in nearly 55 plays with both nationally and internationally renowned theater directors.

Sharma: “I was highly impressed by the script of Amu and by Shonali’s passion. The fact that the story was about the Delhi Riots inspired me to be part of this film. I was in Delhi in 1984 and saw a man burned alive – an image that has been indelible in my mind. The character of Gobind was also something which drew me. I have mostly been typecast as a villain in Hindi films. This was a complex multifaceted role.

Bose: “I auditioned some excellent actors for the role of Gobind. Although not a main lead I felt that Gobind had a key role to play in the script as his life and character captured the poignancy of the long-term impact of 1984. I needed an actor who could make us laugh and who could also make us cry and who also would have a rough raw edge to him. Yaspal blew me away in the audition. He is a brilliant actor and under-utilized in the film industry. He is the only actor in Amu who is from the mainstream film industry.

LOVLEEN MISHRA – LEELAVATI

Lovleen sashayed to fame with her superb portrayal as Chutki in India’s first soap opera Hum Log, which ran on national television from 1984-1987 and was widely watched and loved. She has a rich background in theater and has been a brilliant character actor in many acclaimed films such as Mani Ratnam’s Yuva, Anurag Kashyap’s Black Friday, Roland Joffe’s City of Joy, Govind Nihalani’s Thakshak.

Mishra: “I did Amu primarily for two reasons. First, since Shonali and I go back a long way and as a courtesy to her sister. So I knew she'd make a good sensible film (and she more than proved us right!). Secondly, I saw the havoc the 1984 'engineered' riots played in Delhi, being a Delhi-ite myself. Perhaps some where at the back of my mind, it was my way of doing a bit for all those thousands who were killed, displaced and abused. Last but not the least, the role was interesting.”Bose: “I knew that Lovleen would be sublime as Leelavati and didn’t even ask anyone else. She is truly India’s first woman comedienne. I also knew that she would bring a gravitas to the character and not simply be a cliché village woman. I gave her the freedom to improvise her dialogue, particularly in one scene when she is at the tubewell. she had the entire slum (who were standing all around watching the shooting) and set in splits. I couldn’t call ‘cut’ because I was laughing so much.”

The following actors made their film debut in Amu.

Grandmother - Aparna Roy

Uncle – Ashish Ghosh

Aunt – Ruma Ghosh

Tuki – Chaiti Ghosh

Arun Sehgal (Kabir’s father) – Bharat Kapoor

Meera Sehgal (Kabir’s mother) – Lushin Dubey

Shanno Kaur (Amu’s mother) – Ganeve Rajkotia

Gurbachan (amu’s father) – Kuljeet Singh

The child Amu – Ekta Sood – is a non actor.

|

| FILMMAKER BIOS |

|

Shonali Bose – Writer / Director / Producer

Shonali Bose was born in 1965 and grew up in Calcutta, Bombay and Delhi. She has been an activist since her student days at Miranda House College, Delhi University (BA History Honours) and Columbia University, New York (MA Political Science). Bose was also passionately involved in theater as an actor throughout school and college.

Bose worked for a year as an organizer at the National Lawyer’s Guild, and directed live community television in Manhattan before embarking on the MFA Directing Program at UCLA's School of Theatre, Film, and Television. Her short narrative films (The Gendarme Is Here and Undocumented) and her feature-length documentary (Lifting the Veil) have screened in festivals and other venues throughout the world. As a student at UCLA she received a number of awards: Ely Award for Best Documentary (’97), Wasserman Award (’96), Jack Sauter Award (’95), Hollywood Radio and Television Society International Broadcasting Award (’95), Motion Picture Association of America Award (’94). After graduating from UCLA Bose taught directing at the New York Film Academy and hosted and produced a monthly radio show about South Asia on KPFK. In 2003, she was selected to IFP West’s Project Involve.

Amu is her feature film debut and is written, produced and directed by her. Amu released theatrically in India in January 2005 running to packed houses and receiving popular and critical acclaim. It then went on to premiere at the Berlin and Toronto Film Festivals as well as many other international festivals. Bose has won 7 national and international awards for Amu including the FIPRESCI Critics Award and the National Award for Best Film and Best Director – India’s highest award given by the President of the country. Bose was also asked by Penguin India to convert the Amu screenplay into a novel – which she completed while editing the film. The film and novel were released simultaneously in India on January 7, 2005 making Bose the first Indian to have a simultaneous release of a film and a book.

Bose is currently working on her next script – Chittagong: Strike One. She has already signed some A-list Indian actors for it and is in talks with producers. The film will be shot in winter 2007.The first of a trilogy, it is a Hindi film based in India’s freedom struggle against British colonial rule. She currently lives in Los Angeles with her husband and two sons.

Bedabrata Pain – Executive Producer

Bedabrata Pain, or Bedo as he is commonly called, has been critically involved with the creative, political and financial aspects of Amu from its inception. Married to director Bose, the film is a product of a truly joint effort. Having constantly organized conferences and campaigns on the issue of injustice of 1984 and for the affirmation of rights, he played a critical role in giving final shape to the story. A NASA scientist by profession, Pain is one of the inventors of the active pixel sensor technology that produced the world’s smallest camera in 1995, and led to the digital imaging revolution in the world. This was the invention that provided the seed funding for Amu. In 1997 he was inducted to the US Space Technology Hall of Fame.

Growing up in Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray’s Bengal, literature and music come naturally to Pain. A playwright, singer and activist, he was also the principal researcher for their previous film Lifting the Veil.

“The issue of Delhi 1984 remains very much alive because even after twenty years, it remains a matter of justice denied. It is not possible for India to move forward, if wounds like these are allowed to fester. And the political trend that was set in motion in 1984 continues to haunt the Indian polity.”

|

DELHI 1984 …. |

|

Few people in India – let alone in the world – know that more than 20 years ago, right in the heart of Delhi, the capital city of India, more than 5,000 people of the Sikh faith were murdered in a deadly carnage. Tens of thousands were injured, and many more families were torn apart or dislocated.

|

The massacre took place following the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the prime minister of India on October 31, 1984. Over the next three days, gangs led by politicians and government officials, protected by the police, and armed and abetted by the administration, unleashed a systematic rampage. Had it not been for the citizens of Delhi rising up in defense of their neighbors, many more people would have been massacred Within weeks, independent inquiry commissions courageously compiled extensive reports documenting both the organized nature of the carnage and the role of the officialdom, even as the police and officials refused to register or investigate complaints from the victims and witnesses.

|

Today, after more than two decades, the victims and their families continue to be denied appropriate reparation and rehabilitation. The main perpetrators not only roam free, but enjoy political fortune. This despite the fact that power at the federal level has changed hands nine times since 1984, and nine governmental commissions have come and gone!

The latest governmental commission – the Nanavati commission – did little to reverse the two-decade old course. The report consisting of nebulous references to a possible role by two politicians and one police official, while exonerating the overwhelming majority of the officialdom was squarely rejected as a contemptible attempt at “damage control” and denial of justice

The curtain is yet to fall on what is arguably one of the darkest chapters of Indian history. In contrast with the governmental efforts, a number of groups and activists continue with their initiatives over the years – providing relief and rehabilitation to the victims, fighting legal battles,

|

|

holding independent inquiries and demonstrations, documenting the events in books and booklets.

Thanks to their efforts, the infamy of 1984 cannot be buried or wished away, official efforts to the contrary. Twenty years later, it has become clear that as long as justice is denied for the 1984 massacre, India will remain just as vulnerable to organized bloodshed and continuing cycle of violence.

The status and fate of the nine governmental inquiry commissions:

Ctte. Name |

Date |

Actions |

Ved Marwah Comm. |

Nov. 25, 84 |

Stalled, replaced by Misra Commission |

Misra Commission |

Apr 26, 85 |

Bowing to public pressure, Justice Misra comm. formed. In-camera proceedings. In August 1986, it exonerated the authorities |

Jain-Banerjee Ctte. |

Feb 23, 87 |

Dissolved by the Delhi High Court, before it could give report |

Ahooja Ctte. |

Feb 23, 87 |

Set the death toll to 2,733, although a list of 3,870 people as dead or missing were submitted earlier by CJC |

Kapur-Mittal Ctte. |

Feb 23, 87 |

In 90, KL Mittal identified 72 police officials for organizing the killings |

Poti-Rosha Ctte. |

Mar 27, 90 |

Ctte. Leads resigned after intimidation by the accused |

Jain-Aggarwal Ctte. |

Nov, 90 |

In 93, it submitted a detailed report of covert and overt police actions |

Naroola Advisory Ctte. |

‘94 |

In 95, it recommended cases against the Congress leaders H.K.L. Bhagat and Sajjan Kumar |

Nanavati Commission |

Sept, 05 |

With over 2,500 affidavits detailing the role of leading politicians in the 1984 carnage, Justice Nanavati tries “damage control” by making vague references to possible evidence against two politicians (Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar) and one official (police chief), but exonerating the administration, police, and politicians |

CENSORED!

|

|

It’s September 2004. We race against time to finish Amu and submit it to the Indian Censor Board without whose clearance the film cannot be released. We had planned the release for November 1, 2004 – the 20th anniversary of the 1984 carnage. And we really worked hard to meet this deadline. The censor board delayed it for three months. Finally in December, the verdict was given: five lines of dialogue need to be removed from the film – or redubbed with acceptable dialogue. An “A” Certificate (equivalent to the American NC-17 rating).

The cuts:

Almost all the lines were from the scene where fictional widows explain to the protagonists who exactly organized the “riots”.

“Minister hee to the. Unhee ke shaye pe sab hua”

(It was a Minister. It was all done at his direction).

“Saare shamil the… police, afsar, sarkar, neta, saare”

(They were all involved … the police, the bureaucracy, the government, the politicians – all).

“Hamare adalaton mein to saalon lag jaata hain. Aur uske upar corruption bhi

hai... “

(Our courts take years to resolve anything. And on top of that there is corruption…)

“Aur usne kaha “Saare Sikh ko mar dalo.”

(And he said “Kill all the Sikhs.” - a victim narrating what she overheard a

Minister say.)

In Sikho ko sabak sikhana chahiye.

(These Sikhs should be taught a lesson.)

Instead of changing the lines so that the audience would not be pulled out of the film we took the decision to let the characters go silent. We thought it was a powerful indictment for audiences to see fictional widows in a fictional film silently moving their lips – silenced even after 20 years.

When the film released in India a ripple would go through the audience – “censor, censor” – and in every screening, we were asked what were the lines of dialogue. If ever there were doubts that a cover-up of history had taken place, they were set to rest when the Censor Board explained why they gave the film an “A” certificate. They said, “Why should young people know a history which is best buried and forgotten?”

We made the film because they need to know.

The Censor Board chief, Anupam Kher (a well-known Bollywood actor), was fired in September 2004. He said that he was fired for passing Amu – which was the last film cleared by him.

The government also passed a law that films with an “A” certificate could not be shown on television. In order to show the film on TV – which is the best way for the film to reach a wide audience, we reapplied for a new censor certificate. This time we were given a “U” certificate, but only if we cut a full 10 minutes from the film – picture and sound. If we made the following changes the film would be shown on TV:

Entire riot sequence from when the little girl peeps out till after she calls her mother.

Large parts of the train – hair-cutting sequence

3/4 of the scene where Gobind breaks down and describes how Balbir was killed.

All the dialogue of the man who participated in the riots – Kishan Kumar. He had lines like “You are coming after me because you are scared to go after those people who are behind it who live in big houses and are powerful. But who distributed kerosene to us? Who pointed out the Sikh houses to us by using government electoral rolls?”

With these changes, the film is meaningless. As a result we will not be showing the film on Indian television thus losing not only a significant audience but also the only significant revenue that we could have got from India.

Amu was selected by the AFI Film Festival in Los Angeles for films suitable for the youth. Public school children in LA were able to see Amu. In the Cine Donne Film festival in Torino, Italy, it won the Teenage Choice Award.

The Indian government is not shielding Indian youth from scenes of horrific violence – because there are none in Amu. It was a deliberate aesthetic choice on my part to depict this most grisly massacre without a drop of blood. Today we see so much violence on the TV and in films that we have been inured to it. Amu makes you feel the meaning of violence and death by holding on a close-up of a child’s face watching her father being burned alive, rather than showing the act itself.

The Indian government is shielding its young people from the truth. The cuts they made in Amu for television is equivalent to banning the film. In the 21st century the world’s largest democracy openly and legally carries out political censorship.

This is not acceptable.

AWARDS |

|

National Award, India. Best English Language Film, October 2005

National Award, India. Best Director, English Language Film, October 2005.

FIPRESCI Critics Award, January 2005.

Gollapudi Srinivasa Award – Best Debut Director (India). August 2005.

Star Screen Award – Best English Film (India). January 2006.

Teenage Choice Award, Torino, Italy [Cine donne Film Festival]. October 2005.

Jury Award, Torino, Italy [Cine donne Film Festival]. October 2005.

FESTIVALS |

|

Berlin International Film Festival. February 2005. Official Selection.

Toronto International Film Festival. September 2005. Official Selection.

Kerala International Film Festival. India. December, 2004.

Opening Film - Mumbai Academy of Moving Images Festival (MAMI). India. January, 2005.

Pune Film Festival. India. January 2005.

Durban International Film Festival. South Africa. June 2005.

Calgary International Film Festival. September 2005.

Vancouver International Film Festival. September 2005.

Hamptons International Film Festival. October 2005.

Hawaii International Film Festival. October 2005.

Cine donne Film Festival, Torino, Italy. October 2005.

Opening Gala - Toronto Spinning Wheel Film Festival. October 2005.

AFI International Film Festival, Los Angeles. November 2005.

Indo American Arts Council Film Festival, New York. November 2005.

Sithengi Film Festival, Cape Town, South Africa. November 2005.

River to River Florence Indian Film Festival. Italy. December 2005.

Opening Night - Umang Film Festival. IIT Kanpur, India. January 2006.

Tongues on Fire Film Festival. London. March 2006.

Human Rights Watch Film Festival. London – March 2006. New York – June 2006.

Cleveland International Film Festival. March 2006.

Cinemasia Amsterdam Film Festival. April 2006.

Newport Beach Film Festival. April 2006.

Opening Night – Pittsburgh Asian American Film Festival. May 2006.

High Museum of Art Film Festival of India. Atlanta. May 2006.

Orlando Film Festival. June 2006.

Bollywood and Beyond Stuttgart Film Festival. Germany. July 2006.

Indian Contemporary Cinema. National Art Mueum. Italy. July 2005.

Haifa International Film Festival. Israel. October 2006.

Milwaukee International Film Festival, October 2006.

ACCLAIM |

|

“I loved Amu. It is courageous, honest, compelling. A must see film. And I really commend it and I recommend everyone of us to see it. Because there’s not enough truth on our screens.”

Mira Nair, Filmmaker

“I was profoundly affected by it [Amu]. I really think it is one of the best Indian films I have seen. I have been telling everyone that you are a filmmaker to watch out for. I hope your film gets a release and is seen by everyone."

Deepa Mehta. Filmmaker.

“It is such a powerful and a very brave film. And it deals with a subject that has been an embarrassment to the Government of India and they have never wanted a film or anything to be projected about this. Amu focuses on the point of social justice and the necessity for social justice because that’s the only way you can have peace. Peace is not possible without justice.

It’s an exceptionally well made film and I recommend everyone see this film.”

Shyam Benegal, Filmmaker, MP

“I think Amu is a very very courageous first film. I was deeply moved by the film. Kudos to Shonali for dealing with such a difficult film so sensitively.”

Aparna Sen, Filmmaker. (36 Chowringhee Lane, Mr and Mrs Iyer…)

“As a film, Amu is a revelation… It’s a film about compassion and that’s what touches me; it’s a film about finding yourself and that’s what touches me; it’s a film about discovering the roots of discontent which is what absorbs me into the film. As a first film I salute the filmmaker. It is ambitious and audacious.”

Ketan Mehta, Filmmaker. (The Rising, Mirch Masala…)

“I have stopped crying in films because as a director I am conscious of the filmmaking craft. But Amu was one film which made me forget that I am a director and made me cry. I plead with everyone for the love of cinema that they must see Amu.”

Vishal Bhardwaj, Filmmaker. (Maqbool, Omkara) |

| |

|