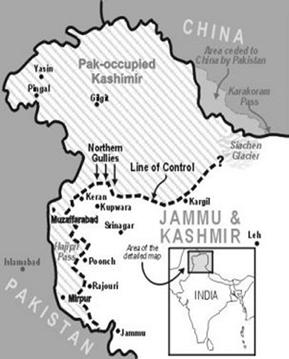

GEOGRAPHY AND GOVERNMENT: Surrounded by mountains, the southern two-thirds of the Valley is Indian Jammu and Kashmir (“J&K”), India’s northernmost state, bordering Tibet and China. Northwest is Azad (or “free”) Kashmir – a self-governing state under Pak control. The Valley is 84 miles long, 25 wide: 10% of J&K’s 84,000 sq miles. Over 50% of the population is in the Valley. A 1972 treaty renamed the 550-mile border the Line of Control. Only two roads lead in and out of Srinagar, the capital of J&K.

PREVIOUS HISTORY: J&K was cobbled together by the Hindu Dogra ruler Ghulab Singh, who acquired the Valley from the British in 1846, adding it to Ladakh and Jammu. Singh created an ethnically and religiously diverse state ruled by a religious minority. Today J&K’s population exceeds 13 million, with over 1 million inhabiting Srinagar; 95% of the Valley is Muslim, equally Sunni and Shia.

CONFLICTS SINCE 1947: Ghulab Singh’s great-grandson kept the princely state of J&K intact and independent until October 1947, when, after modern India and Pakistan were formed, Pakistan invaded and he chose to join the state with India: conflicts ensued. Indo-Pak wars over Kashmir were fought in 1949, 1965, 1971, 1990, and 2002. From 1989-1996 mercenary guerrillas fought occupying CRPF (Indian army). Every year since 2006 unarmed civilians have led bloody uprisings against the CRPF.

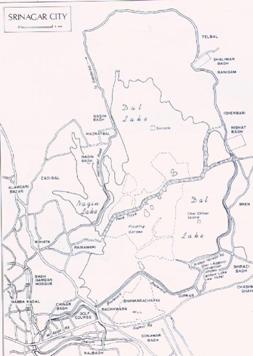

LIFE IN THE VALLEY: The spoken language is Kashmiri, which has no alphabet of its own and is written in Urdu. Virtually all signage is in English, which only 25% of Kashmiris can read given the state’s confirmed 75% illiteracy. The CRPF that controls the Valley are Hindu and speak Hindi, causing friction. The main industry is tourism – which caters to a mostly Western and Indian clientele – and whose signature is its houseboats on Dal Lake. The three continuing, crippling threats to tourism are political violence, blackouts (e.g. separatist strikes and government curfews), and the decline of Dal Lake. J&K’s economy has never risen above 1% of India’s total yearly GDP.

DAL LAKE: Sitting in the center of Srinagar at 7,000 feet above sea-level, Dal has sustained Kashmir’s entire civilization; its tourism, its fisheries, and – in another Indo-Pak dispute – its hydro-electric power grid. Due to pollution and climate change, the lake’s future is dire.

Srinagar, Kashmir in the news

Kashmir’s Fruits of Discord

The New York Times, November 8, 2010

By ARUNDHATI ROY

A WEEK before he was elected in 2008, President Obama said that solving the dispute over Kashmir’s struggle for self-determination — which has led to three wars between India and Pakistan since 1947 — would be among his “critical tasks.” His remarks were greeted with consternation in India, and he has said almost nothing about Kashmir since then.

But on Monday, during his visit here, he pleased his hosts immensely by saying the United States would not intervene in Kashmir and announcing his support for India’s seat on the United Nations Security Council. While he spoke eloquently about threats of terrorism, he kept quiet about human rights abuses in Kashmir.

Whether Mr. Obama decides to change his position on Kashmir again depends on several factors: how the war in Afghanistan is going, how much help the United States needs from Pakistan and whether the government of India goes aircraft shopping this winter. (An order for 10 Boeing C-17 Globemaster III aircraft, worth $5.8 billion, among other huge business deals in the pipeline, may ensure the president’s silence.) But neither Mr. Obama’s silence nor his intervention is likely to make the people in Kashmir drop the stones in their hands.

I was in Kashmir 10 days ago, in that beautiful valley on the Pakistani border, home to three great civilizations — Islamic, Hindu and Buddhist. It’s a valley of myth and history. Some believe that Jesus died there; others that Moses went there to find the lost tribe. Millions worship at the Hazratbal shrine, where a few days a year a hair of the Prophet Muhammad is displayed to believers.

Now Kashmir, caught between the influence of militant Islam from Pakistan and Afghanistan, America’s interests in the region and Indian nationalism (which is becoming increasingly aggressive and “Hinduized”), is considered a nuclear flash point. It is patrolled by more than half a million soldiers and has become the most highly militarized zone in the world.

The atmosphere on the highway between Kashmir’s capital, Srinagar, and my destination, the little apple town of Shopian in the south, was tense. Groups of soldiers were deployed along the highway, in the orchards, in the fields, on the rooftops and outside shops in the little market squares. Despite months of curfew, the “stone pelters” calling for “azadi” (freedom), inspired by the Palestinian intifada, were out again. Some stretches of the highway were covered with so many of these stones that you needed an S.U.V. to drive over them.

Fortunately the friends I was with knew alternative routes down the back lanes and village roads. The “longcut” gave me the time to listen to their stories of this year’s uprising. The youngest, still a boy, told us that when three of his friends were arrested for throwing stones, the police pulled out their fingernails — every nail, on both hands.

For three years in a row now, Kashmiris have been in the streets, protesting what they see as India’s violent occupation. But the militant uprising against the Indian government that began with the support of Pakistan 20 years ago is in retreat. The Indian Army estimates that there are fewer than 500 militants operating in the Kashmir Valley today. The war has left 70,000 dead and tens of thousands debilitated by torture. Many, many thousands have “disappeared.” More than 200,000 Kashmiri Hindus have fled the valley. Though the number of militants has come down, the number of Indian soldiers deployed remains undiminished.

But India’s military domination ought not to be confused with a political victory. Ordinary people armed with nothing but their fury have risen up against the Indian security forces. A whole generation of young people who have grown up in a grid of checkpoints, bunkers, army camps and interrogation centers, whose childhood was spent witnessing “catch and kill” operations, whose imaginations are imbued with spies, informers, “unidentified gunmen,” intelligence operatives and rigged elections, has lost its patience as well as its fear. With an almost mad courage, Kashmir’s young have faced down armed soldiers and taken back their streets.

Since April, when the army killed three civilians and then passed them off as “terrorists,” masked stone throwers, most of them students, have brought life in Kashmir to a grinding halt. The Indian government has retaliated with bullets, curfew and censorship. Just in the last few months, 111 people have been killed, most of them teenagers; more than 3,000 have been wounded and 1,000 arrested.

But still they come out, the young, and throw stones. They don’t seem to have leaders or belong to a political party. They represent themselves. And suddenly the second-largest standing army in the world doesn’t quite know what to do. The Indian government doesn’t know whom to negotiate with. And many Indians are slowly realizing they have been lied to for decades. The once solid consensus on Kashmir suddenly seems a little fragile.

I WAS in a bit of trouble the morning we drove to Shopian. A few days earlier, at a public meeting in Delhi, I said that Kashmir was disputed territory and, contrary to the Indian government’s claims, it couldn’t be called an “integral” part of India. Outraged politicians and news anchors demanded that I be arrested for sedition. The government, terrified of being seen as “soft,” issued threatening statements, and the situation escalated. Day after day, on prime-time news, I was being called a traitor, a white-collar terrorist and several other names reserved for insubordinate women. But sitting in that car on the road to Shopian, listening to my friends, I could not bring myself to regret what I had said in Delhi.

We were on our way to visit a man called Shakeel Ahmed Ahangar. The previous day he had come all the way to Srinagar, where I had been staying, to press me, with an urgency that was hard to ignore, to visit Shopian.

I first met Shakeel in June 2009, only a few weeks after the bodies of Nilofar, his 22-year-old wife, and Asiya, his 17-year-old sister, were found lying a thousand yards apart in a shallow stream in a high-security zone — a floodlit area between army and state police camps. The first postmortem report confirmed rape and murder. But then the system kicked in. New autopsy reports overturned the initial findings and, after the ugly business of exhuming the bodies, rape was ruled out. It was declared that in both cases the cause of death was drowning. Protests shut Shopian down for 47 days, and the valley was convulsed with anger for months. Eventually it looked as though the Indian government had managed to defuse the crisis. But the anger over the killings has magnified the intensity of this year’s uprising.

It was apple season in Kashmir and as we approached Shopian we could see families in their orchards, busily packing apples into wooden crates in the slanting afternoon light. I worried that a couple of the little red-cheeked children who looked so much like apples themselves might be crated by mistake. The news of our visit had preceded us, and a small knot of people were waiting on the road.

Shakeel’s house is on the edge of the graveyard where his wife and sister are buried. It was dark by the time we arrived, and there was a power failure. We sat in a semicircle around a lantern and listened to him tell the story we all knew so well. Other people entered the room. Other terrible stories poured out, ones that are not in human rights reports, stories about what happens to women who live in remote villages where there are more soldiers than civilians. Shakeel’s young son tumbled around in the darkness, moving from lap to lap. “Soon he’ll be old enough to understand what happened to his mother,” Shakeel said more than once.

Just when we rose to leave, a messenger arrived to say that Shakeel’s father-in-law — Nilofar’s father — was expecting us at his home. We sent our regrets; it was late and if we stayed longer it would be unsafe for us to drive back.

Minutes after we said goodbye and crammed ourselves into the car, a friend’s phone rang. It was a journalist colleague of his with news for me: “The police are typing up the warrant. She’s going to be arrested tonight.” We drove in silence for a while, past truck after truck being loaded with apples. “It’s unlikely,” my friend said finally. “It’s just psy-ops.”

But then, as we picked up speed on the highway, we were overtaken by a car full of men waving us down. Two men on a motorcycle asked our driver to pull over. I steeled myself for what was coming. A man appeared at the car window. He had slanting emerald eyes and a salt-and-pepper beard that went halfway down his chest. He introduced himself as Abdul Hai, father of the murdered Nilofar.

“How could I let you go without your apples?” he said. The bikers started loading two crates of apples into the back of our car. Then Abdul Hai reached into the pockets of his worn brown cloak, and brought out an egg. He placed it in my palm and folded my fingers over it. And then he placed another in my other hand. The eggs were still warm. “God bless and keep you,” he said, and walked away into the dark. What greater reward could a writer want?

I wasn’t arrested that night. Instead, in what is becoming a common political strategy, officials outsourced their displeasure to the mob. A few days after I returned home, the women’s wing of the Bharatiya Janata Party (the right-wing Hindu nationalist opposition) staged a demonstration outside my house, calling for my arrest. Television vans arrived in advance to broadcast the event live. The murderous Bajrang Dal, a militant Hindu group that, in 2002, spearheaded attacks against Muslims in Gujarat in which more than a thousand people were killed, have announced that they are going to “fix” me with all the means at their disposal, including by filing criminal charges against me in different courts across the country.

Indian nationalists and the government seem to believe that they can fortify their idea of a resurgent India with a combination of bullying and Boeing airplanes. But they don’t understand the subversive strength of warm, boiled eggs.

BETWEEN THE MOUNTAINS

The New Yorker, March 11, 2002

By ISABEL HILTON

When the French doctor François Bernier entered the Kashmir Valley for the first time, in 1665, he was astounded by what he found. “In truth,” he wrote, it “surpasses in beauty all that my warm imagination had anticipated. It is not indeed without reason that the Moghuls call Kachemire the terrestrial paradise of the Indies.” The valley is sumptuously fertile. Along its floor, there are walnut and almond trees, orchards of apricots and apples, vineyards, rice paddies, hemp and saffron fields. There are woods on the lower slopes of the surrounding mountains—sycamore, oak, pine, and cedar. The southern side is bounded by the Pir Panjal, not the highest mountain range in Asia but one of the most striking, rising abruptly from the valley floor. The northern boundary is formed by the Great Himalayas. At the heart of the valley lie Dal Lake and the graceful capital, Srinagar.

For Europeans, Kashmir became a locus of romantic dreams, inspiring writers like the Irish poet Thomas Moore, who didn’t even need to visit it to understand its charms. “Who has not heard of the Vale of Cashmere,” he wrote in 1817, “with its roses the brightest that earth ever gave.” So seductive was this landlocked valley that, like a beautiful woman surrounded by jealous lovers, Kashmir attracted a succession of invaders, each eager to possess her.

The Moghuls established their control in the sixteenth century. Kashmir became the northern limit of their Indian empire as well as their pleasure ground, a place to wait out the summer heat of the plains. They built gardens in Srinagar, along the shores of Dal Lake, with cool and elegantly proportioned terraces—with fountains and roses and jasmine and rows of chinar trees. The Moghul rulers were followed by the Afghans and, later, by the Sikhs from the Punjab, who were driven out in the nineteenth century by the British, who then sold the valley, to the abiding shame of its residents, for seven and a half million rupees to the maharaja, Gulab Singh. Singh was the notoriously brutal Hindu ruler of Jammu, the region that lay to the south, beyond the Pir Panjal, on the edge of the plains of the Punjab.

Under Singh, the Kashmir Valley was conjoined in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. According to one calculation of the purchase, the ruler of the newly formed state had bought the people of Kashmir for approximately three rupees each, a sum he was to recover many times over through taxation. For the maharaja and his descendants and their visitors, the valley was a luxurious paradise; they enjoyed fishing and duck shooting, boating excursions on Dal Lake, picnics in the hills and the saffron fields, moonlit parties in the magnificent gardens. In the penetrating cold of the winters, the visitors, and the maharaja, left the valley to itself and returned to Jammu.

Kashmir was also a natural crossroads. The Silk Route, with its great camel trains from China, passed to the north, and the country’s mountain passes opened routes to the Punjab, Afghanistan, and Jammu. Through them successive intruders brought different cultures that added layers to Kashmir’s own. The Kashmiri language was a mixture of Persian, Sanskrit, and Punjabi; the handicrafts for which the valley was celebrated were Central Asian; and the religious faith was variously Buddhist, Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim. Sufi masters left a legacy of music and tolerance in their Muslim teachings. A Sikh who had lived many years in Srinagar described the culture of the valley as an old cloth so covered in patches that you can’t see the original.

Today, the valley is predominantly Muslim, but, as part of the maharaja’s portmanteau state of Jammu and Kashmir, it still shares its destiny with other faiths and peoples: the Hindus of Jammu, the Buddhists of Ladakh, as well as Gilgits and Baltis, Hunzas and Mirpuris. There had been conflicts between the communities in the past, but by the mid-twentieth century Kashmir was an unusually tolerant culture. It escaped the intercommunal violence that Partition brought to the neighboring Punjab when the British left the subcontinent, in 1947. Kashmir’s violence was to occur later, as the two new states of India and Pakistan became the latest of Kashmir’s neighbors to fight over it.

Today, Kashmir is partitioned—Pakistan controls slightly less than a third, India some sixty per cent, and China the rest. Most of Kashmir’s twelve million people are concentrated in Indian-held territories, and the rest are mainly in Pakistan-held ones; relations among its many communities are now marked by mutual mistrust. And since the late eighties a bewildering number of combatants have fought a savage, irregular war that, in a steady daily toll of killing, has cost, depending on whom you believe, between thirty to eighty thousand lives. On the side of the Indian state, the participants include the local police, the Border Security Force, the Central Reserve Police Force, and the Army, supported by various intelligence organizations and a motley group of turncoat former militants who have muddied the public understanding of who, over the years, has done what to whom. Opposing them are a proliferation of Islamic militant groups. At one time, there were more than sixty of them. Several are fundamentalist and deadly—like the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, which are based in Pakistan (and have been listed as terrorists by the United States) and were recently banned by Pakistan’s President Pervez Musharraf. The largest group, the Hizbul Mujahideen, is Muslim but not, its supporters insist, fundamentalist, and most of its activists, who number around a thousand, are Kashmiris.

Surrounding the insurgency is the wider, implacable hostility between India and Pakistan. But at its core is the story of a people who, for five centuries, have been longing to call their homeland their own. Last October, I was permitted to go into what Pakistan calls Azad (“Free”) Kashmir, a territory that Pakistan maintains is truly autonomous but which depends entirely on the country’s military and money for its continued existence. India calls the territory Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. The entity has existed ever since Pakistan wrested this northwest third of the original state of Jammu and Kashmir from Indian control in a war that followed the 1947 Partition. For Pakistan, that war was the first step toward a liberation of Kashmir’s Muslims from India. Once liberated, Pakistan hoped, the Kashmiris would join Muslim Pakistan.

At the time of Partition, Jammu and Kashmir was still ruled by a Hindu maharaja, Hari Singh, a descendant of Gulab Singh. The maharaja was one of five hundred and sixty-two fabulously rich feudal monarchs whom the British had manipulated in order to maintain their grip on much of India. At Partition, these states were given a choice of joining India or Pakistan. Independence was not on offer. Most joined India. The maharaja dithered for months, unable to decide between two equally unattractive options. As a Hindu, he did not like Pakistan. As an Indian, he did not like the British. As a prince, he cared neither for the antifeudal Mahatma Gandhi nor for the local Muslim leader, Sheikh Abdullah, who favored autonomy for Kashmir but without its maharaja. Then, on October 20, 1947, armed tribesmen and regular troops from Pakistan invaded Kashmir. The maharaja appealed to India for support and hastily agreed to sign the now famous Instrument of Accession to India: the state of Kashmir and Jammu was accepted as part of the new federal union of India; in exchange, it was, exceptionally, granted a semiautonomous status. (India would control only matters of defense, foreign affairs, and communications; everything else was to be run by Jammu and Kashmir’s own parliament.) Pakistan, furious, refused to accept the legality of the accession, and Pakistan and India fought their first war over Kashmir.

In Pakistan, what is remembered was a promise made by the Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to hold a plebiscite in which the people of Kashmir could make their preferences clear. That plebiscite was never held. India blames Pakistan: in 1949, after a ceasefire was agreed to under United Nations supervision, Pakistan failed to withdraw from Azad Kashmir, a betrayal that, India says, vitiated the commitment to the plebiscite.

Today, there are few routes that connect Azad Kashmir with Pakistan proper.

[In the mountain village of Chakothi] tensions were unusually high. The United States bombing of Afghanistan had begun, and the military’s view was that India might take advantage of the situation—troop movements had been detected. Yaqub’s list of the casualties incurred in the last thirteen years of what he saw as Kashmir’s freedom struggle against India was startling, even if undoubtedly exaggerated: 74,625 killed, 80,317 wounded, 492 adults burned alive, 875 schoolchildren burned alive, 15,812 raped, 6,572 sexually incapacitated, 37,030 disabled, and 96,752 missing --- |