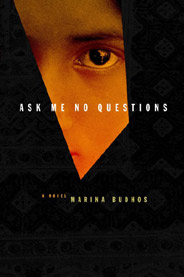

Ask Me No Questions

by Marina Budhos

WE DRIVE AS IF IN A DREAM.

Up I-95, past the Triborough Bridge, chunks of black ice floating in the East River. Me and Aisha hunched in the back, a green airline bag wedged between us filled with Ma's luchis and spiced potatoes. Abba in the front, clutching the steering wheel, Ma hunched against the rattling door.

We keep driving even as snowflakes clump on the wipers, and poor Abba can barely see. Coconut flakes, Ma jokes. We'll go outside and scoop them up, and I'll make you some polao. But the jokes lie still in our throats.

Up the East Coast, past all these places I've seen only in maps: Greenwich, New Haven, Providence, Rhode Island. Hour after hour, snow slanting down. And in my head, words keep drumming: Special Registration. Deportation. Green card. Residency. Asylum. We live our lives by these words, but I don't understand them. All I know is we're driving straight through to that squiggle of a line on the map, the Canadian border, to apply for asylum.

Unspoken questions also thud in our minds. What happens if we get stopped and they see Abba's expired license? Should Ma wear slacks and a sweater so she doesn't stand out so much? Should Aisha drive, even though it's supposed to be a secret that she knows how? We ask some of these questions out loud, and others we signal through our eyes.

When we reach Boston, Aisha wakes up and starts to cry. That's where she's hoped she'd live one day. Aisha always knew that she wanted to be a doctor going to Harvard Medical School. Even back in Dhaka she could ace her science and math exams, and when Abba was in Saudi Arabia working as a driver, he used to tape her reports to his windshield and boast about his daughter back home who could outdo all the boys. In those days Abba wasn't afraid, not of anything, not even the men who clucked and said Aisha would be too educated to find a husband, or the friends who worried that he'd be stuck with me, his fat and dreamy second daughter. Sometimes I hate being the one who always has to trail after Aisha. But sometimes it feels safe. I'm nestled in the back, not seen.

Ma pats Aisha on the hand. "Don't worry," she whispers. "All this, it's just for a while. We'll get you in to a university in Canada."

"McGill!" Abba booms from the front seat. "A top-rate school!"

"It's too cold!" I complain.

Aisha kicks me. "Shut up," she hisses, then speaks softly to my father's back. "Whatever you say, Abba." Aisha and I, we never hit it off, really. She's the quick one, the one with a flashing temper whom Abba treats like a firstborn son, while I'm the slow-wit second-born who just follows along. Sometimes I think Abba is a little afraid of Aisha. It's like she always knew what she wanted, and he was put on this earth to answer her commands. Back in Dhaka when Abba wasn't sure about going to America, she cut out an article and put it in his lap: a story about a Bangladeshi girl who'd graduated top of her class in economics and now worked for the World Bank.

"We may be one of the poorest countries in the world," she told Abba. "But we're the richest in brains."

Abba laughed then. Where did an eight-year-old learn to say such things?

That's the way it always was. Oh, did you hear what the teacher said about Aisha today? "Your sister!" The other girls would whisper to me. "She's different." But what kills me is that Aisha always says the right thing. She asks Ma if she's low on mustard oil for cooking, or Abba if he asked the doctor about the better ointment for his joints.

It's hard to have a sister who is perfect.

In Portland, Maine, Abba pulls into a gas station. He looks terrible: Dark circles bag around his eyes. He's wearing one of his favorite sweater vests, but after ten hours on the road it looks lumpy and pulled. Ma scrambles out of the car to use the bathroom. As she pushes across the station, I notice the pale bottom of her shalwar kameez flutter up around her jacket. She presses it down, embarrassed. The attendant is staring at her, the gas pump still in his hand. He's Sikh, with soft, almond shaped eyes, and he smiles at her sweetly, as if he understands, and Ma gets up her nerve and pushes inside the metal door.

After, she takes one look at the two of us and says softly, "We need to stop for some food. These poor girls, they look faint."

When we go inside the small diner, Ma looks funny sitting in the booth, drawing her cardigan across her chest, touching her palms to the ends of her hair. Even though Aisha and I hang out at Dunkin' Donuts and McDonald's all the time, my family rarely goes out to restaurants. Ma's always afraid that they'll ask her something and the English words won't come out right. Now she glances around nervously, as if she expects someone to tap us on the shoulders and tell us to leave. "What if they say no at the border?" she whispers. "What if Canada turns us down?"

Abba sighs, wearily rubbing his eyes. "It could happen. No one guarantees asylum."

We've been over this again and again. We know the risks. If Canada turns us down for asylum, we have to go back across the American border, and Abba will probably be arrested because our visas to America have long since run out. And then we don't know what could happen. Maybe one day we will get U.S. residency. Or maybe we'll just be sent back to Bangladesh. But maybe--just maybe--Canada will let us in.

Abba continues, "Look, Aisha has to begin university in the fall. This is for the best." But he doesn't sound so sure.

Aisha leans her head on Ma's shoulder, her frizzy hair falling in a tumble over her cheeks. "Don't worry, Ma. It'll be okay. We'll get to Toronto and you'll open your restaurant, right?"

A little burn of envy sears right through me. I don't know how Aisha does it, but she always cheers up my parents. Ma and Aisha look a lot alike: They're both fair skinned and thin, and they're these incredible mimics. Ma's always picking things up from TV, where she's learned most of her English.

"Abba, why don't you tell us a story?" Aisha asks.

Abba sits back, his fingers resting lightly on the Formica tabletop, his face relaxed.

I should have asked that. After all, it's usually me who sits around with the elders listening to their stories. Nights when Aisha's in her room studying, I'll sit curled next to Abba and Ma, my head against their legs, and they'll tell me about Bangladesh and our family. Even though we left when I was seven, sometimes if I close my eyes, it's as if I were right there. I remember the boroi tree outside our house, the stone wall where Ma slapped the wash dry, the metal cabinet where Abba kept his schoolbooks. Abba carries his stories carefully inside him, like precious glass he cradles next to his heart.

"I'll tell you about the stationery."

We all grin. We've heard this story before, but it's comforting--like sinking into the dense print of one of the old books Abba brought with him from Bangladesh.

"Your great-grandfather used to work as a printer. When he was old and ready to return to our village, the man he worked for gave him a box of the best stationery with his own name printed across the top. Grandfather used to keep that stationery in a special box with a lock. Even when he was old and blind, sometimes he brought it out, and we children would run our fingers over the raised print. Grandfather never wrote anyone with those pages. Who was he going to write to on that fine stationery with the curvy English print?

"After I saw your mother, I wanted to impress her. So I sneaked into my grandfather's room, and I stole a sheet of paper, used my best inkwell and pen, and copied out a beautiful poem. When Grandfather found out, he was furious!"

"Were you punished?" I ask.

Abba nods. "I was, and rightly so. Not only did I deceive my grandfather, but I was not off to a very good start with your mother! She thought I was a rich man who could write poetry. But I was only a poor student who could copy from books." He glances over at Ma. "And I'm still a poor man!"

"Hush," Ma scolds. But I can see she is pleased. She looks gratefully at Aisha, and my stomach twists with jealousy.

"Are you done with those?" I ask, pointing to the last of my sister's fries.

Her nose wrinkles. "No, greedy girl." And she pops the rest into her mouth.

I remember when we first arrived at the airport in New York, how tight my mother's hand felt in mine. How her mouth became stiff when the uniformed man split open the packing tape around our suitcase and plunged his hands into her underwear and saris, making us feel dirty inside. Abba's leg was jiggling a little, which is what it does when he's nervous. Even then we were afraid because we knew we were going to stay past the date on the little blue stamp of the tourist visa in our passports. Everyone does it. You buy a fake social security number for a few hundred dollars and then you can work. A lot of the Bangladeshis here are illegal, they say. Some get lucky and win the Diversity Lottery so they can stay.

Once we got here, Abba worked all kinds of jobs. He sold candied nuts from a cart on the streets of Manhattan. He worked on a construction crew until he smashed his kneecap. He swabbed down lunch counters, mopped a factory floor, bussed dishes in restaurants, delivered hot pizzas in thick silver nylon bags. Then Abba began working as a waiter in a restaurant on East Sixth Street in Manhattan. Sixth Street is lined with Indian restaurants, each a narrow basement room painted in bright colors and strung with lights with some guy playing sitar in the window. They're run by Bangladeshis, but they serve all the same Indian food, chicken tandoori and biryani, that the Americans like. Every night Abba brought home wads of dollars that Ma collected in a silk bag she bought in Chinatown.

The thing is, we've always lived this way--floating, not sure where we belong. In the beginning we lived so that we could pack up any day, fold up all our belongings into the same nylon suitcases. Then, over time, Abba relaxed. We bought things. A fold-out sofa where Ma and Abba could sleep. A TV and a VCR. A table and a rice cooker. Yellow ruffle curtains and clay pots for the chili peppers. A pine bookcase for Aisha's math and chemistry books. Soon it was like we were living in a dream of a home. Year after year we went on, not thinking about Abba's expired passport in the dresser drawer, or how the heat and the phone bills were in a second cousin's name. You forget. You forget you don't really exist here, that this really isn't your home. One day, we said, we'd get the paperwork right. In the meantime we kept going. It happens. All the time.

Even after September 11th, we carried on. We heard about how bad it had gotten. Friends of my parents had lost their jobs or couldn't make money, and they were thinking of going back, though, like my father, they'd sold their houses in Bangladesh and had nothing to go back to. We heard about a man who had one side of his face bashed in, and another who was run off the road in his taxi and called bad names. Still people kept coming for pooris and alu gobi on Sixth Street; still Abba emptied his pockets every night into Ma's silk bag. Abba used to say, "In a bad economy, people want cheap food. Especially cheap food with chili peppers that warms their bellies."

But things got worse. We began to feel as if the air had frozen around us, trapping us between two jagged ice floes. Each bit of news was like a piece of hail flung at us, stinging our skins. Homeland Security. Patriot Act. Code Orange. Special Registration. Names, so many names of Muslims called up on the rosters. Abba had a friend who disappeared to a prison cell in New Jersey. We heard of hundreds of deported Iranians from California and others from Brooklyn, Texas, upstate New York. We watched the news of the war and saw ourselves as others saw us: dark, flitting shadows, grenades blooming in our fists. Dangerous.

Then one day my cousin Taslima's American boyfriend came over and explained the new special registration law and how every Muslim man must register with the government. Some did, and were thrown in jail or kicked out of the country. More and more we heard about the people fleeing to Canada and applying for asylum there, instead of going into detainment. Abba's friends came over in twos and threes. Ma served them sweets and doodh-cha--milky tea--and they'd talk. About starting again in the cold country up north. A new life. The Canadians are friendly, they liked to say.

"There comes a time," Abba said grimly, "when the writing is right there on the wall. Why should we wait for them to kick us out?" He added, "I want to live in a place where I can hold my head up."

One evening Abba came into our bedroom, a quiet, sad look on his face. "Take that down," he said to Aisha. He was pointing to her Britney Spears poster, the only one she was allowed. Ma opened the closets and folded all her saris and shalwar kameezes into the nylon suitcases we used when we came here. We could tell no one--not even our best friends at school--what we were doing.

Abba asked me to bring out my map of the northeast. After I laid the map open on the dining table, Abba showed us the thick arteries of highways, the spidery blue line of the border. "There," he said. "We have to go there and apply for asylum."

I swallowed, my throat very dry. What happens if they don't let us in? I kept thinking.

The next morning we woke to a scraping and coughing noise and saw the blue Honda by the curb.

By the time we get on the road again the day is in full swing. Tractor trailers are roaring out of the lot, and there's a pink tinge to the sky. It looks like more snow though--up ahead, when we turn onto the highway, we can see the gray clouds massed on the horizon. When Abba cracks open the window, icy wind slices across my cheek.

We go silent in the car. This is the last stretch, past the signs for Bass shoe outlets and cigarettes sold cheap. We're going to leave the main highway soon and stop at the immigration station on the border between Vermont and Canada and tell them we're asking for asylum.

We'll fill out some forms and it will take a long time, but then they'll let us go to the other side.

The landscape here is different: clapboard houses with slanted roofs, church spires, white-columned buildings. I'd always heard about New England. At the college office in our high school there are lots of catalogues with the kids sitting on lawns in front of buildings like this. When I see those pictures I want to press myself inside. Just like I want to go to Disney World and Las Vegas and play the slot machines, though Ma would freak. One day I was watching The Simpsons and they did this really funny show about Epcot Center. But I can't even laugh at places like that because first I have to go there. Then I can laugh and be sort of above it all. That's how you can tell the immigrant kids from the ones born here. We don't laugh about those places. We just want to go.

The road has turned foggy. The trees sweep past in a wet blur. Abba's driving very slow, hunched over the wheel, trying to peer through the windshield.

We pass a sign: LEAVING THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. I see Abba's hand pause as he grabs his chest, rubbing. It hurts, this leaving. We weren't supposed to do this. We were supposed to stay and then one day roll the word in our mouths: home. Every inch the car moves forward the word seems to crack, crushed under our tires.

Our car slows and we see four--no, seven--no, maybe a dozen cars ahead of us. Around the bend a Greyhound bus is letting out lots of people: men in long white kurta--knit scarves around their necks--and women whose shalwar kameezes stick out from their sweaters. Everyone is stamping their feet in the cold. Just beyond is a low brick building, the red and white Canadian flag snapping on a pole.

A tall man in a brown uniform and hat is moving toward us, waving his gloved hand. Slowly Abba lets down the window.

"Officer, sir?" he asks.

The tip of the man's nose is rosy red, and he's got gingery freckles all over his cheeks. "Passports?" He says it as if he knows not to bother.

"We are applying for asylum in your country, sir," Abba replies. Ma is leaning forward to the left so sharply, I think she's going to fall into Abba's lap.

The man shakes his head, droplets spattering off the brim of his hat. "Sorry. We're full up here. Overwhelmed. People have been coming nonstop, and we can't process them all."

We're still swallowing down the cold, unable to speak. I can see Ma's eyes start to crinkle and turn shiny-wet.

"But sir, we can drive to another post. You just tell me where--"

He shakes his head again. I can see it is a friendly move--he looks sorry to have to say no. "Everywhere. Detroit. All the border crossings. It's been crazy these past few weeks."

No one says a word. I can hear Ma crying very quietly.

From the back Aisha pipes up, "What do you recommend?"

The man takes her in: a seventeen-year-old girl with kohl smudged around her eyes and her frizzy black hair spilling around her parka hood. She's wearing a Destiny's Child T-shirt and jeans my Ma always says are too tight on her.

"The best thing you can do is go back around the American side. I'm afraid they'll probably arrest you if your visa isn't current--" Here he looks at Abba, who is staring dully at the windshield. "My guess is it won't be all of you. I hear they're asking for around five thousand dollars bond. If you put that together, you can come back in a few weeks and try to apply for asylum again."

Abba is squeezing the steering wheel, open-shut, open-shut, just like the massage exercises he did after he got hurt on his construction job. He's hunched over, still as a rock, as if he can't make himself move.

"Sir?"

Still Abba doesn't answer.

"Sir, if you could just turn the car around that way?"

Slowly, Abba puts the car into reverse.

It's funny how long it can take to arrest a person. You'd think it would be like on TV: badges flashing, guns, handcuffs clinked around my dad's wrists. Instead we drive back through the American side, show our passports with the expired visas, and pull around to a low building. We stand on line for hours under fluorescent lights that make my eyes itch, and then, after they look at the papers, they tell Abba to wait. We wait and doze on metal folding chairs, and then they explain everything we already know: Abba would be taken into detention and deportation proceedings might begin. The rest of us can go, and if we come up with the five thousand dollars, Abba will be released and he can apply for asylum on the Canadian side. It could be weeks, though, before they even open our files. Ma digs into her pocketbook and finds numbers of a couple of churches that have shelters which will put us up in Burlington--Taslima, my cousin, found those for her before we left.

Abba, who has taken this all in very quietly, turns to us. He looks first at me, and folds down the collar of my jacket. Then he touches Aisha's hair, once.

"Aisha, Nadira. You are going back."

"Back?" Aisha asks.

He shakes his head. "This is not some kind of quick-quick thing. It could take weeks. And I don't want these children missing school, stranded up here in this cold place. Aisha is about to graduate. She has to finish her year and prepare for college. You want all that to go out the window?"

"How will we get there?"

Abba lets a slow, crooked smile cross his face. "You'll drive."

So Abba knew about her secret driving lessons all along.

"But what about me?" Ma asks.

"You will stay here, at the shelter." He hands her the small silver oval of a cell phone, closes his palm over hers. "You keep this to be in touch with everyone. When the paperwork is done, we'll send for the children."

I feel as if Abba has sliced the air in two, leaving a ragged gap between them and us. Go back without them? And live where? And how?

Abba lifts the Chinese silk bag out of his coat pocket and hands it to Aisha. "You go stay with Auntie. This is the money for your upkeep. You go to school, you don't say a word to anyone. You do your homework, and you help out in the house. Understand?"

I do understand. That's the way it has always been. Go to school. Never let anyone know. Never.

Aisha is nodding, tears streaming down her face. Abba has cupped a hand around her chin and is speaking softly to her. "You understand I'm doing this for you, nah?"

Still crying, Aisha bobs her head up and down, and I feel that same sharp cut inside. Why is it always Aisha's future?

"Sir?" It's the officer who did all the processing and very quietly explained that Abba would have to go into the detention area until we posted bond. She's holding a thick folder under her arm, and she looks very tired.

Abba stands up, smoothes his palms over knees. "All right, then," he says in a husky voice. "Time to go."

Now everything happens so fast. I keep thinking that this is a videotape, and any minute now the screen will go blank, and we can rewind and wake up in our apartment and start the day again.

We divvy up the clothes in the suitcases.

"I need a coat," Ma suddenly announces. "If I'm going to stay in this godforsaken place, I need a better coat."

"Ma, where are we going to find you a coat now?" Aisha asks. "We don't even know where the mall is."

"No mall," she replies. "Salvation Army."

Sometimes Ma surprises me. I didn't even know that she knew what the Salvation Army was. But as we were driving into town, Ma's sharp eyes spotted the red-and-white sign of the thrift store. She is already counting her dollars, stretching what she has.

Soon enough we're combing through racks of coats that smell of dust and old perfume, the pockets stuffed with crumpled tissues and old tickets. I try not to think about Abba in the big concrete room with wooden benches, or about the long, lonely drive ahead. Aisha is holding up coat after coat: a navy blue one with fake white fur trim, a brown tweed with big, deep pockets. Ma doesn't like any of them. "I have to look a certain way," she keeps muttering. "I'm there for your father. I show up in court. I have to look a certain way."

"What way?" we keep asking her, but she just shakes her head, her long braid swinging at her back.

And then she finds it: a purple coat with large, glossy, black buttons and huge flap of a collar. When Ma puts it on, the coat flares out about her hips like a tent. She swirls around in front of the dirty mirror, laughing. "That's it! I saw a TV show the other day about Jacqueline Kennedy, you remember? Bad things happen to her, and she always looks so nice and trim in public. I always thought if I had to be a white lady, I would want to look like her."

"You and everyone else," Aisha laughs.

But it is good seeing Ma happy for a moment. We find her a pair of galoshes made of milky plastic that she can pull up over her shoes. And the best thing is the whole deal costs us $18.50.

Outside the shelter Ma walks us to the car. She's already put on the coat and I swear it makes her look different--ready to be brave and crisp in front of those immigration authorities. Before we get in she pulls each of us near, presses her cold palms to our cheeks. "You be good," she says.

Aisha has started up the car. As I get into the passenger seat, I see Ma in that purple coat, pressing the black buttons to her chin, those silly galoshes flapping open over her ankles.

Button them up, I want to tell her, but Aisha has swerved the car away.

The sky over Burlington looks like it's made of clear blue glass. I think of Abba behind the cross-wire fence, the way his face broke into wrinkles when he'd heard the news of his detainment. Abba loves this country in his own way; it's like this bowl he carries in his heart--so full, so ready to trust. And right now, as we head to the highway, all I can hear is the sound of his heart shattering.