movies.rediff.com |

An advertising executive and filmmaker, Benegal has made socially relevant films like Ankur, Nishant, Manthan and Bhumika. After winning India's prestigious Dadasaheb Phalke lifetime achievement award, he had laughingly protested that he was not finished with filmmaking. You have worked in New York -- in the Children's Television Workshop? It was more in Boston than here. Here, I was just observing. I was working in Boston. Did your experiences help shape your filmmaking in any way? No, no, no. It was just that I wanted to extend my own experience. Funding has always been an issue in the kind of films you've made. It's been an issue from the beginning and continues to be an issue even now. So you always have to work out the strategies to be able to make the kind of money you need to make good films. And you have to work hard on different kind of methodologies, tactics -- all sorts of things. How is it now? Now it's become a little easier than it used to be -- not just for me, but for younger people. It's become much less problematic than it used to be then. That's largely because there's more screens playing and you can get more screen space for a film. What was screen space to do with it? Screen space was a huge, huge issue, because when you made a film if you didn't have the natural magnets of stars, it would be a huge problem. The theatres used to be very big. In the ratio between the exhibitor, distributor and producer, the producer got the least amount. The man who took the least risk got the most money: The exhibitor. Then came the distributor, then came the producer. It meant that if you had a 1,000-seat cinema, the break-even point was that 800 seats had to be sold. That's a helluva lot! And if you couldn't get 800 -- even if you filled the theaters with 700 people -- you were losing. You were losing with 700 people coming to your movie! That was the kind of economics you were fighting at that time. But with the multiplexes having come in today, theatre themselves are 200-300 seaters. And even if you sell 20 tickets or 30 tickets, you're still okay. And it's much more equitable sharing. This has made a difference and the economics of filmmaking has changed to that extent. 'I was historically lucky'

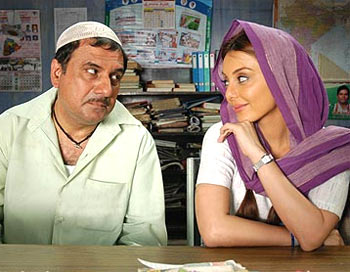

But, just as much as there's the positive thing, there's also the negative thing. Films are much more expensive to make, and star prices have hit the roof, largely because corporates have come in. They have deep pockets and they think they can cover [ground] by saturation marketing. But you know the corporate market well... My last film is made by a corporate entity anyway: Well Done, Abba, my latest film, has been made by Reliance. That's a very big entity in films now. The last one was made for UTV, which is another corporate entity. The advantage when you make with corporates is that you don't have a problem of releasing the film. The films will get released. If you don't have that kind of backing, you make a small picture [that] does not cost much [but] if you're not going to get a release it's a problem. But how did you arrange funding for yourself when a lot of your fellow filmmakers lost out? Many of these things started as accidents, really, because my first producer -- he produced, altogether, five of my films -- was an advertising film distributor. Because of that he had a network. He had a lien on 200-300 theatres all over the country. So when I made a film there was an assurance that it would definitely be released. That's more than half the battle won. Then it is a question whether the film is picked up by the audience or not. But you have to reach it to the audience. A lot of young filmmakers [in the 1970s] who were making films with me didn't have that [covered]. Many of them had films that remained unreleased. So in that sense I was historically lucky. And that was it? There was another advantage at that time. In 1972-1973, [India] had a foreign exchange problem. When she first became prime minister [Indira Gandhi] had to take some unpalatable decisions. She had to devalue the Indian currency, we were short of food, [had] many terrible problems. During that time the government of India decided that those people making money in India, like Hollywood film companies, could only repatriate about 15 to 20 percent of the money made in India. Hollywood rebelled. [That created a bigger slot for local cinema]. 'Anurag Kashyap is a huge talent'

It's based on many things. I shot in [cartoonist] Mario Miranda's house, a mansion built in the 1680s. There's a lot of history to that house. It's played a fairly important part in the historical life of Goa. The story of the house itself I incorporated into the storyline. You tried interesting experiments in that, including the use of natural lighting... And in the narrative style of the film... What would you think young people need to be aware of in filmmaking? They seem to be doing extremely well for themselves. Greater opportunities. Of course, frustrations will always be there. They're caught in another kind of a trap. What happens is that corporates will allow them to make any film they want -- but there is a kind of formulaic idea that [as long as] you take a star, it doesn't matter what film you make. So they have to convince a film star to act in their film -- and that can take a lot of energy out of you. Young non-resident Indian directors like Sangeeta Datta are making films, too... Sangeeta doesn't face the same kind of problem because she operates from London. Like Diasporic directors here, their problems are way different from the problems of filmmakers in India. But of the young filmmakers, who do you think is making interesting cinema in India? Anurag [Kashyap, who directed Black Friday, Dev D, and Gulaal]. I mean, he's a huge talent. He and Vishal Bhardwaj [Makdee, Maqbool, Omkara]. 'Naseeruddin, Om Puri made a huge name but they were not 'stars' like Shah Rukh or Aamir'

It's like this. I've been around for a long time. So there is a kind of brand loyalty. I have an audience but it would be worth a certain amount of money. But if I had to do a film that requires a budget bigger than that, that becomes a problem. Then I will need to rely on getting a star or something. Is there a particular actor who stood out? There are many. Look at Rajat Kapoor. There are any number I can mention: Ila Arun, Neena Gupta, Pallavi Joshi. They all moved to television because that is more lucrative. In the younger generation, they are all hugely talented but they are all jostling for the top. But there are greater opportunities in television. Even people like Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri made a huge name but they were not 'stars' like Shah Rukh Khan or Aamir Khan. So that way there are very few stars in the Indian film industry. You have not considered making a film, say, with Aamir Khan? If they want to work with me. Sometimes they may be interested in doing [a film] but they may worry the kind of film I might make with them will take them out of their star image... It may only harm them. You have made a lot of serious social scripts but now you're dealing with the same themes using more... I have found you can engage an audience better with comedy and you can deal with tough, unpalatable, the most depressing of subjects. If you approach it with humour [you can get across easier]. But there is nobody in the film industry... Who's doing any of that. But that depends on whether they are interested or not. They don't appear to be. Who doesn't? Many of the younger people. But some of them do because at festivals here there are people who are making socially concerned [films]. This is an interesting film festival because they all come together in one place. Otherwise, they get dispersed and we don't even know that many of these wonderful films are being made. |

| Source: http://movies.rediff.com/slide-show/2009/nov/18/slide-show-1-shyam-benegal-on-the-effects-of-corporate-funding.htm |

Award-winning director Shyam Benegal was at the Mahindra Indian Indo-American Arts Council film festival in New York.

Award-winning director Shyam Benegal was at the Mahindra Indian Indo-American Arts Council film festival in New York.  So things are much easier now?

So things are much easier now? You're related to Guru Dutt, who made a film on Goa [Baaz], just as you did, using a story you yourself wrote [Trikaal]. A Goan story is unusual in Indian cinema...

You're related to Guru Dutt, who made a film on Goa [Baaz], just as you did, using a story you yourself wrote [Trikaal]. A Goan story is unusual in Indian cinema... You have introduced actors like Shabana Azmi, who have gone on to mainstream cinema, and you've taken mainstream stars like Karisma Kapoor.

You have introduced actors like Shabana Azmi, who have gone on to mainstream cinema, and you've taken mainstream stars like Karisma Kapoor.